| Notes: Continuous traffic growth in the later years of the nineteenth century underlined the need for improving the Admiralty Pier which was open to the elements. The plans for Admiralty Pier were amended in 1906 to allow the building of a new station for the South Eastern & Chatham Railway on reclaimed land on the north side of the pier. This would replace the existing station on the Pier which was always susceptible to closure during heavy seas.

Dover Harbour, which is generally acknowledged to be one of the greatest feats of port construction at that time, was completed in 1909. The walls and piers were built of large blocks weighing from 30 to 40 tons. These blocks were made of concrete, with a granite facing to those that were to be placed on the outside surfaces of the walls above water level. The completed harbour was opened on 14 October 1909 by H.R.H. the Prince of Wales, the future King George V. In 1909 work started on the new station to create an artificial platform for the new terminus alongside the north end of the Admiralty Pier. Dover Harbour, which is generally acknowledged to be one of the greatest feats of port construction at that time, was completed in 1909. The walls and piers were built of large blocks weighing from 30 to 40 tons. These blocks were made of concrete, with a granite facing to those that were to be placed on the outside surfaces of the walls above water level. The completed harbour was opened on 14 October 1909 by H.R.H. the Prince of Wales, the future King George V. In 1909 work started on the new station to create an artificial platform for the new terminus alongside the north end of the Admiralty Pier.

Creating sufficient land for the new terminus involved the construction of a sea wall made out of concrete blocks to the east of the Admiralty Pier. Large quantities of chalk were then dumped into the water between the pier and the new wall with the pier becoming the western side of the new station site. 1,200 ferroconcrete piles were manufactured on site; up to 75ft in length and of 17in diameter. These were driven down through the chalk into the original seabed; this process avoided having to wait for the dumped chalk to settle. The heads of the piles were connected by reinforced concrete slabs.

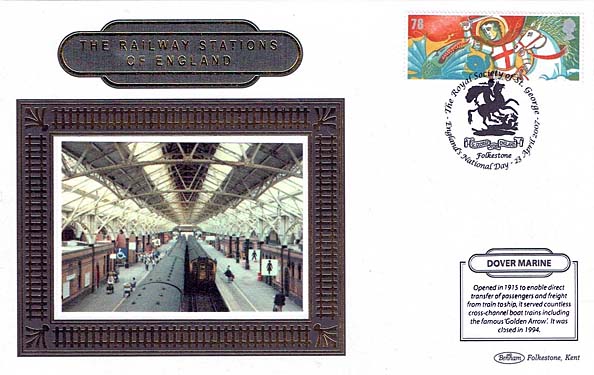

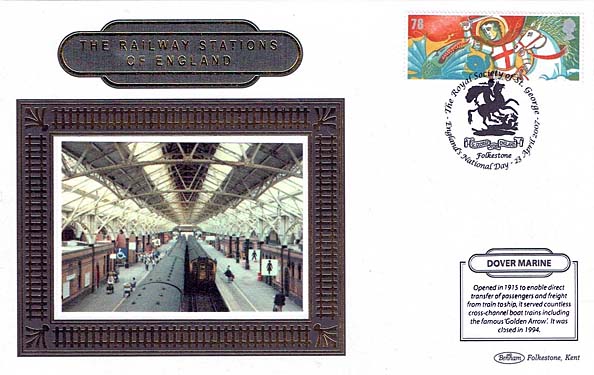

Once the reclamation of the 12-acre site had been completed construction of the terminus started in 1913. It comprised a steel and glass cathedral roof (trainshed) 800ft in length and 170ft wide. Beneath the trainshed there were two 60ft-wide concrete island platforms, each 693ft in length.

The station was largely completed in 1914 but with the start of WW1 the continental ferry service ceased to operate as a wartime economy measure. Dover Town station closed on 14 October 1914 with all services being diverted to Dover Harbour and Dover Priory. Admiralty Pier and the new terminus were taken over for military use with the new station opening as Dover Admiralty Pier, for military traffic only, on 2 January 1915 when it became the principal ambulance railway station. During the early years of the war the station was still in an unfinished state.

From January 1915 onwards the port of Dover was the main evacuation port for wounded soldiers. Between January 1915 and February 1919 it is estimated that 1,260,000 wounded and ailing soldiers passed through the port and were dispatched to all parts of England, Wales and Scotland from the station. From July 1917 overseas leave and draft men were conveyed to the Western Front via the port of Dover. These additional troop movements continued unabated until February 1919 when the facilities in Dover were finally turned over to the civilian authorities.

Repatriated British prisoners of war started to arrive at Dover on 17 November 1918. By February 1919 180 boats conveying 55,398 released former POWs were received by 130 trains. In January 1919 the large Customs Examination Shed in the station was utilised for the sorting out of demobilised men, who began to arrive at Dover. The number passing through Dover amounted to 720,664 servicemen. When the armistice came in November 1918, the SE&CR had a fine record of war service to its credit, and Field Marshall Sir Douglas Haig wrote the following letter of commendation to Cosmo Bonsor, the Chairman of the SE&CR Managing Committee: ‘The Army in France owes much to all connected with the control of our railway companies in the United Kingdom, and indeed in the Empire. They have at all times shown great willingness to help us in every possible way in their power. Track has been torn up to give us rails, engines, trucks, men, capable engineers, operations staff all have been sent abroad to us, regardless of their own special needs and demands of the people at home, and without a moment’s hesitation. But we have been more closely associated with the South Eastern & Chatham Railway than any other. The bulk of our ammunition and stores required for the maintenance of our armies, as well as several millions of men as reinforcements and on leave, have passed over their system. Their sphere of duty, too, has been nearest to the shores of France and Belgium, and consequently more open to hostile attacks by air and fear of invasion by sea. Undisturbed by any alarms the traffic for the Armies in France has never ceased to flow. This reflects the greatest credit on all concerned with the company’. Repatriated British prisoners of war started to arrive at Dover on 17 November 1918. By February 1919 180 boats conveying 55,398 released former POWs were received by 130 trains. In January 1919 the large Customs Examination Shed in the station was utilised for the sorting out of demobilised men, who began to arrive at Dover. The number passing through Dover amounted to 720,664 servicemen. When the armistice came in November 1918, the SE&CR had a fine record of war service to its credit, and Field Marshall Sir Douglas Haig wrote the following letter of commendation to Cosmo Bonsor, the Chairman of the SE&CR Managing Committee: ‘The Army in France owes much to all connected with the control of our railway companies in the United Kingdom, and indeed in the Empire. They have at all times shown great willingness to help us in every possible way in their power. Track has been torn up to give us rails, engines, trucks, men, capable engineers, operations staff all have been sent abroad to us, regardless of their own special needs and demands of the people at home, and without a moment’s hesitation. But we have been more closely associated with the South Eastern & Chatham Railway than any other. The bulk of our ammunition and stores required for the maintenance of our armies, as well as several millions of men as reinforcements and on leave, have passed over their system. Their sphere of duty, too, has been nearest to the shores of France and Belgium, and consequently more open to hostile attacks by air and fear of invasion by sea. Undisturbed by any alarms the traffic for the Armies in France has never ceased to flow. This reflects the greatest credit on all concerned with the company’.

Much of the north end of Admiralty Pier was incorporated into an extensive network of trackwork and sidings around the new station; these were required to handle the large quantity of freight traffic passing through Dover during the war. Access to the station and sidings was controlled by a large 120-lever SE&CR-designed signal box on the down side approach to the station. The two platforms were spanned by a lattice footbridge at the north end of the trainshed. Much of the north end of Admiralty Pier was incorporated into an extensive network of trackwork and sidings around the new station; these were required to handle the large quantity of freight traffic passing through Dover during the war. Access to the station and sidings was controlled by a large 120-lever SE&CR-designed signal box on the down side approach to the station. The two platforms were spanned by a lattice footbridge at the north end of the trainshed.

Although the trainshed was virtually complete, construction of the stone façade at the north end had not been started. Once completed this comprised an ashlar frontage with rusticated dressings. The central section had a large central round-headed opening for two tracks with rusticated surround and enriched keystone with the inscription above 'S E and C R'. There were flanking full-height narrow rusticated arches within which were high circular windows above pedestrian entrances. The rusticated surrounds rose to an interrupted cornice with blank cartouches in the parapet. The flanking lower bays had rusticated round-headed arches and end quoins each for a single track. The sides and rear of the building were of red brick with some ashlar dressings. The south-east elevation had pilasters at regular intervals and some black brick dressings. Pedestrian access was through a detached entrance block opposite the ‘Lord Warden’ hotel. This comprised a tall three-bay single-storey building with doorways flanking a central window. The north-west side, facing the hotel, had patterned stonework with quarry faced quoins. The three openings had stone arching (voussoirs). There was a decorative cornice with a slate French pavilion roof and a circular window. The return bays had round-headed windows flanked by rusticated engaged Tuscan columns and the remainder was of brick with stone dressings. A wide stairway led up to a 455ft-long enclosed glazed footbridge which was suspended above the double track of the former Admiralty Pier. The footbridge was divided down the middle with cast iron railings to separate people going on to the pier, who used the west side, while passengers for the station used the east side. The sides of the walkway were constructed of steel with elliptical roof trusses and had continuous windows.

On each platform there were three large blocks of brick buildings, each 100ft in length and 25ft in width. These buildings were allocated to a variety of purposes, including waiting rooms, tea rooms, dining and refreshment facilities, post and parcel shed railway staff rooms etc. At the end of each platform nearest to the Admiralty Pier provision was made for a Post Office, and at the end of the other platform there was a Customs Examination and Clearance Shed. On each platform there were three large blocks of brick buildings, each 100ft in length and 25ft in width. These buildings were allocated to a variety of purposes, including waiting rooms, tea rooms, dining and refreshment facilities, post and parcel shed railway staff rooms etc. At the end of each platform nearest to the Admiralty Pier provision was made for a Post Office, and at the end of the other platform there was a Customs Examination and Clearance Shed.

After WW1 the SE&CR erected a war memorial on the platform in tribute to the 5,222 staff and employees of the South Eastern & Chatham Railway who served in HM forces during the war; of those who served, 556 men lost their lives.

A 4-road carriage shed, open at both ends, was built on the west side of the trainshed. It was 700ft long by 63ft wide and intended for cleaning carriages and the minor servicing of locomotives. It was a notoriously unpleasant place to work, especially in south-west gales at high tide. On such occasions the waves would come over the pier parapet, cross the open tracks and pour down through the various holes in the roof. In later years the salt water would often cause an electrical short circuit on the insulator pots under the conductor rails which then sometimes exploded! The shed could be entered through a doorway in the trainshed wall.

With the restoration of continental services after the war the new station was renamed Dover Marine in 1918 and opened for passenger traffic with the first boat train arriving on 18 January 1919. In 1926 Admiralty Harbour was recognized as having limited military use and it was decided to hand it, including the Admiralty Pier, to the Dover Harbour Board for administration as a commercial undertaking. The only facilities for locomotives were a turntable and water tank sited behind the signal box.

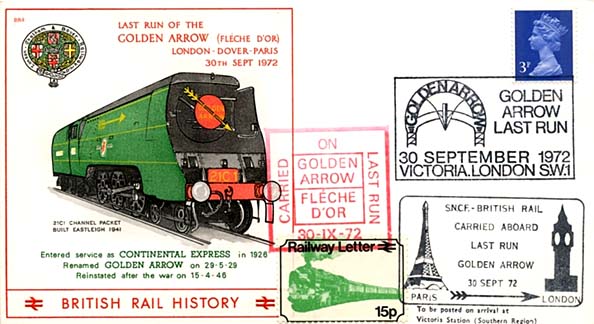

On 14 November 1924 the 'Continental Express' boat train was introduced and consisted of the six first class Pullman cars, a baggage and brake van. It left London Victoria at 10.50 am, the return 'Continental Express' train leaving Dover for London at 5.30 pm. On 14 November 1924 the 'Continental Express' boat train was introduced and consisted of the six first class Pullman cars, a baggage and brake van. It left London Victoria at 10.50 am, the return 'Continental Express' train leaving Dover for London at 5.30 pm.

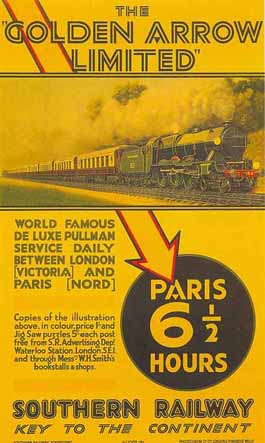

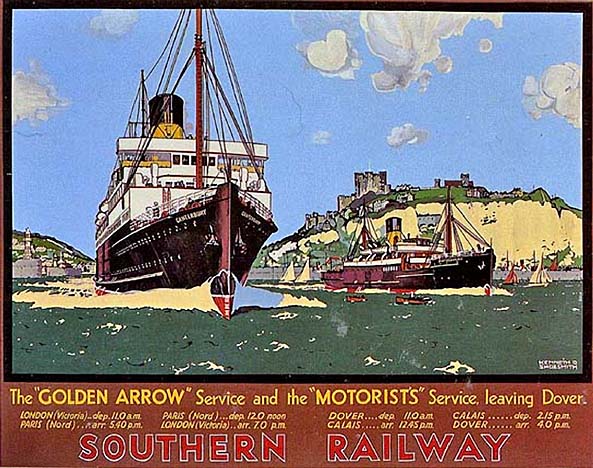

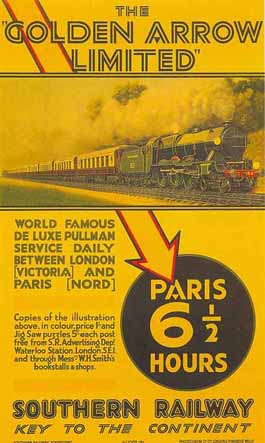

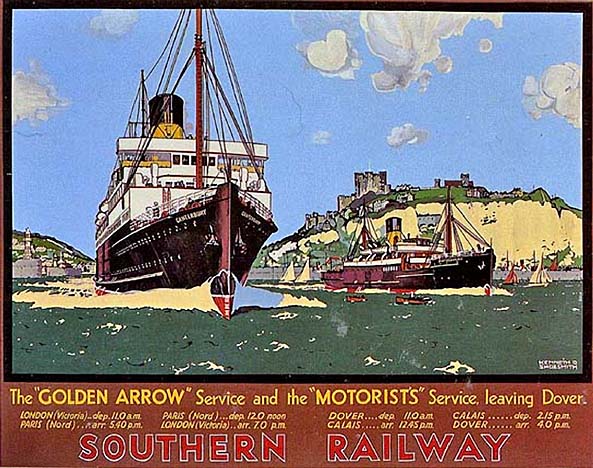

The Southern Railway introduced the ‘Golden Arrow’ service on 15 May 1929. As noted above, they had already introduced the ‘Continental Express’ boat train on 14 November 1924 which was designed to give extra comfort. That train consisted of six first class Pullman cars, a baggage and a brake van and left London Victoria at 10.50 am with the return Continental Express train leaving Dover for London at 5.30 pm. The French, in September 1926, followed Southern’s lead and launched an all-Pullman train between Paris and Calais, giving it the title of ‘Flèche d’Or’ (Golden Arrow). To take passengers across the Channel, Southern had ordered a vessel to be known as ‘Canterbury’ from William Denny & Brothers of Dumbarton. In the meantime, the company decided to upgrade the ‘Continental Express’ with a new train given the anglicised name of the ‘Golden Arrow’.

The ‘Golden Arrow’ consisted of 10 Pullman cars, hauled by a 4-6-0 Lord Nelson class or King Arthur class engine sporting a Union Flag and Tricolour. At the time the Lord Nelson class was introduced, in 1926, they were the most powerful engines in Great Britain. The carriages were individually named, resplendent in chocolate and cream and aimed exclusively at first class Pullman passengers. On board was the ‘Trianon’ cocktail bar, a converted twelve-wheeled Pullman, modelled on a high-class club for the rich. The train also boasted the first public address system and passengers were addressed in both English and French.

The ‘Canterbury’ was launched on 13 December 1928 at Dumbarton and arrived in Dover on 30 April 1929, commencing service on 15 May, the same day as the ‘Golden Arrow’. The journey between London and Paris was advertised to take 6½ hours and each day the ‘Golden Arrow’ was scheduled to depart London Victoria at 11.00 am and reach Dover Marine station at 12.38 pm. As the line is fairly level with a very long straight section, speeds of 60 mph were not unknown. Having crossed the Channel in the ‘Canterbury’ and on reaching Calais the passengers were transferred to the awaiting ‘Flèche d’Or’, a four-cylinder Nord Pacific of the French Northern railway, arriving in Paris at 5.35pm UK time. The single fare was £6.10s. The ‘Canterbury’ was launched on 13 December 1928 at Dumbarton and arrived in Dover on 30 April 1929, commencing service on 15 May, the same day as the ‘Golden Arrow’. The journey between London and Paris was advertised to take 6½ hours and each day the ‘Golden Arrow’ was scheduled to depart London Victoria at 11.00 am and reach Dover Marine station at 12.38 pm. As the line is fairly level with a very long straight section, speeds of 60 mph were not unknown. Having crossed the Channel in the ‘Canterbury’ and on reaching Calais the passengers were transferred to the awaiting ‘Flèche d’Or’, a four-cylinder Nord Pacific of the French Northern railway, arriving in Paris at 5.35pm UK time. The single fare was £6.10s.

When the original cross-Channel sleeper service was introduced in 1869 passengers were required to catch the train in London, alight in Dover at the Admiralty Pier, embark on the night sleeper ferry, disembark at the Continental port and then catch a train to Paris or Brussels.

To run a service where a passenger could stay in the same compartment between London and a Continental capital without alighting was problematic owing to Dover’s tides. The maximum difference between high and low tides at Dover is some 23ft; however, by the 1920s advances in technology appeared to make such a service possible. Southern Railway, in the UK and the Société de Navigation Angleterre-Lorraine-Alsace in Belgium agreed to build a train ferry dock in Dover, outside the Tidal Basin, between South Pier and Admiralty Pier a short distance to the north-east of Dover Marine station.

The specifications, drawn up by George Elson, Chief Engineer of Southern Railway, were a concrete dock 414ft long and 72ft wide, with a minimum depth of water of 17ft to a maximum of 36ft. Construction work started in August 1933 and two railway lines were laid to connect the dock to the main line into Dover Marine. The Southern Railway commissioned three purpose built ferries from Swan, Hunter & Wigham Richardson of Newcastle upon Tyne. Each ship was designed to take 12 sleeping cars, 500 passengers during the day, or approximately 40 goods wagons. There was also a small floor above the train deck to accommodate approximately 20 cars. The specifications, drawn up by George Elson, Chief Engineer of Southern Railway, were a concrete dock 414ft long and 72ft wide, with a minimum depth of water of 17ft to a maximum of 36ft. Construction work started in August 1933 and two railway lines were laid to connect the dock to the main line into Dover Marine. The Southern Railway commissioned three purpose built ferries from Swan, Hunter & Wigham Richardson of Newcastle upon Tyne. Each ship was designed to take 12 sleeping cars, 500 passengers during the day, or approximately 40 goods wagons. There was also a small floor above the train deck to accommodate approximately 20 cars.

On 28 September 1936 the first trains were shunted aboard the SS ‘Hampton Ferry’ which was decorated with flags and bunting for the opening of the terminal with many distinguished guests making the return crossing to Calais. The night service between London and Paris was officially inaugurated by the French Ambassador on 5 October 1936. The train left Victoria Station at 11.00 pm and arrived in Paris at 8.55 am the following day. The counterpart left Paris for London and there was a daily goods service via the ferry. A new daily service was launched during the night of 5 October 1936. The 'Night Ferry' was an international sleeper train between London Victoria and Paris Gare du Nord (and later also Brussels). It was operated jointly by the SNCF and the Southern Railway

Facilities for the shipment of cars to and from the Continent by the train-ferry service were launched on 28 June 1937, when a ramp connecting the shore with the steamer was used for the first time.

On 14 January 1939 Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax travelled by way of Dover Marine, using the ‘Golden Arrow’ and the ‘Canterbury’, for Rome. This was to meet with Benito Mussolini, Italian Prime Minister and leader of the National Fascist Party, in an effort to persuade him not to become involved in the pending conflict. World War II was declared on 3 September 1939. Following the ‘Golden Arrow’s’ last trip, the ‘Canterbury’ left Dover for conversion into a troop carrying ship. The ship ‘Invicta’ was built in 1939 to take over from the ‘Canterbury’ but she was also commandeered for war work following her launch in 1940. On 14 January 1939 Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax travelled by way of Dover Marine, using the ‘Golden Arrow’ and the ‘Canterbury’, for Rome. This was to meet with Benito Mussolini, Italian Prime Minister and leader of the National Fascist Party, in an effort to persuade him not to become involved in the pending conflict. World War II was declared on 3 September 1939. Following the ‘Golden Arrow’s’ last trip, the ‘Canterbury’ left Dover for conversion into a troop carrying ship. The ship ‘Invicta’ was built in 1939 to take over from the ‘Canterbury’ but she was also commandeered for war work following her launch in 1940.

Although the ferry service was once again curtailed the station remained operational handling hundreds of special trains during the Dunkirk evacuation. On peak days some 60,000 men boarded special trains. All told nearly 200,000 British and Allied troops passed through Dover. Consistent shelling made it unsafe for the station to handle any kind of passenger traffic. On 12 May, during the evacuation, the town and port was declared a ‘Protected Area’, and following the evacuation Marine Station was closed with passenger services along the former SER route into Dover terminating at Folkestone. In June 1941 the station was reopened to military traffic going to the Second Front following Germany’s invasion of Russia. On 7 June 1940 the engine shed near Marine station received a direct hit with one serious injury. The Marine station came in for sustained shelling and on 25 September and on 12 September 1944 there was substantial damage to the roof during an air raid.

After the war the Marine station was handed back to Southern Railway and another plaque was added to the station’s war memorial stating: 'And to the 626 men of the Southern Railway who gave their lives in the 1939-1945 war’. The passenger ferries returned; on demobilisation, the ‘Invicta’ was converted to oil fuel having been originally designed to use Kent coal. She was fitted with radar and on 10 October 1946 came to Dover to take over the ‘Golden Arrow’ service. Pre-war passenger numbers were never regained owing to the popularity of the car, and when new car ferry services were introduced the number of rail passengers using the ferries dropped dramatically.

To accommodate 12-car multiple-unit trains when the electrification from London via, Faversham started in June 1959, the two island platforms at Dover Marine were extended by 114ft, with 24ft ramps. The extensions comprised prefabricated concrete components, manufactured at Exmouth Junction concrete works. This necessitated altering the layout of the tracks at the London end and the construction of a riveted steel footbridge across the approach tracks from Dover Priory, linking the main entrance beside the ‘Lord Warden’ hotel with the Customs Hall, on the northern perimeter of the Western Docks. The bridge ran from the landing at the top of the stairs from the street entrance opposite the hotel. To accommodate 12-car multiple-unit trains when the electrification from London via, Faversham started in June 1959, the two island platforms at Dover Marine were extended by 114ft, with 24ft ramps. The extensions comprised prefabricated concrete components, manufactured at Exmouth Junction concrete works. This necessitated altering the layout of the tracks at the London end and the construction of a riveted steel footbridge across the approach tracks from Dover Priory, linking the main entrance beside the ‘Lord Warden’ hotel with the Customs Hall, on the northern perimeter of the Western Docks. The bridge ran from the landing at the top of the stairs from the street entrance opposite the hotel.

During this work the station was closed for one week at the end of February 1959, and it reopened on 1 March. During that period cross-Channel services were diverted to Folkestone, apart from the car and train ferries, which worked as usual as the tracks to the train ferry dock were not affected. By the end of the week the track work had been completed, and the spans of the footbridge were erected. The full width of the extended platforms between tracks 3 and 4 and tracks 5 and 6 was provided with a W-shaped canopy without a valance for weather protection as it was outside the trainshed. A relay room was built alongside the signal box for the colour light signals that were brought into use with the electrification.

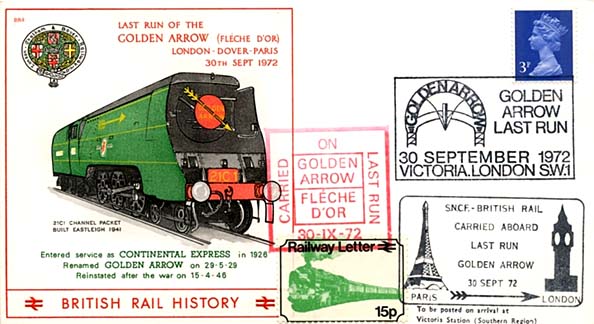

Steam trains were still seen at the station after electrification as the Folkestone line was not electrified until 18 June 1962. Despite the new electrified service in face of further stiff competition from the car in the 1960s, the ‘Invicta’ made her last ‘Golden Arrow’ sailing on 8 August 1972, and the last ‘Golden Arrow’ train ran on 30 September that year.

Dover Marine was renamed Dover Western Docks on 14 May 1979, and although its future seemed secure the ‘Night Ferry’ was withdrawn on 31 October 1980. By this time the carriages were outdated and in need of replacement; they were not air conditioned, and during the ship voyage, while inside the ship, they became notably hot in summertime. This was exacerbated by the chaining of the vehicles to the ship's deck, an activity underneath the sleeping compartments which inevitably woke most passengers during the middle of the night. The carriages were over 40 years old and, by some margin, were the oldest passenger vehicles running on the British network. Dover Marine was renamed Dover Western Docks on 14 May 1979, and although its future seemed secure the ‘Night Ferry’ was withdrawn on 31 October 1980. By this time the carriages were outdated and in need of replacement; they were not air conditioned, and during the ship voyage, while inside the ship, they became notably hot in summertime. This was exacerbated by the chaining of the vehicles to the ship's deck, an activity underneath the sleeping compartments which inevitably woke most passengers during the middle of the night. The carriages were over 40 years old and, by some margin, were the oldest passenger vehicles running on the British network.

By mid 1985 the rails in the trainshed had been cut back at the south end to create a ground level passenger walkway behind the new buffers. A headshunt was, however, retained until 1992. Although the ferries were still well used at this time, when the first Channel Tunnel boring began on 1 December 1987 it soon became clear that the station's days were numbered. The carriage shed to the west of the station was demolished in the mid 1980s and a new line was laid through the site to Admiralty Pier. Closure of the station was announced in a BR report published in 1989 titled 'Proposed closure of Dover Western Docks Station and Folkestone Harbour branch'. It was clear from the report that passenger ferries were an outdated mode of transport as the Channel Tunnel would be able to cater for all passenger requirements with a much faster and more efficient service. Any freight that could not be handled by the tunnel, such as chemicals and inflammable products, would be transferred to the Eastern Docks which were not rail-connected.

On 25 September 1994 Dover Western Docks station was closed following the completion of the Channel Tunnel and concentration of remaining Dover ferry services on the Eastern Docks. After 'official' closure the station continued to be used by unadvertised passenger trains to Faversham until 19 November 1994 after which date they were classified as empty stock movements. After closure the station remained in operational use for train berthing and cleaning purposes. All rail movements finally came to an end on 5 July 1995 with the closure of the signal box.

Demolition and track-lifting commenced at the beginning of 1996. The Dover Harbour Board had hoped to demolish everything to build a new cruise terminal but the trainshed and the entrance building on Lord Warden Square were Grade II listed by English Heritage on 22 June 1989 so the only demolition related to the platform extensions that had been added in 1959. Demolition and track-lifting commenced at the beginning of 1996. The Dover Harbour Board had hoped to demolish everything to build a new cruise terminal but the trainshed and the entrance building on Lord Warden Square were Grade II listed by English Heritage on 22 June 1989 so the only demolition related to the platform extensions that had been added in 1959.

The trainshed was converted into a cruise liner terminal; this included filling the trackbed up to platform level to create car parking. All the buildings within the trainshed were retained as was the covered footbridge to the pedestrian entrance. Although not part of the listing, the signal box was also retained as offices although it was eventually demolished in 2000.

Dover's £10 million Cruise Terminal (now known as Cruise Terminal 1) was opened in June 1996 by the Chairman and Chief Executive of Cunard Line during a visit by the ‘Royal Viking Sun’. Dover Cruise Port is the second largest such port in the UK and in 2006 carried approximately 190,000 passengers travelling with 37 different cruise lines.

Along with the removal of much of the old railway infrastructure at Dover Western Docks in 1979, the ‘Night Ferry’ enclosed dock was filled in and is now used as an aggregates terminal. An attempted resurrection of British–Continental sleeper services under the Nightstar (a play on Eurostar) brand after the opening of the Channel Tunnel in 1994 was abandoned after many of the coaches (night coaches, sleepers, and food service cars) for it had been built. Competition from cheap airlines in the 1990s meant the service could never be profitable, and the proposed service faced daunting logistical problems as well. The coaches were never used in Europe; they were sold to Canada's Via Rail.

Route maps drawn by Alan Young. Tickets from Michael Stewart except 0068 and 2590 Brian Halford. Bradshaw from Nick Catford.

Special thanks to the Dover Historian web site for help with this feature.

Click here to see a film of a train journey between Folkestone Junction and Dover Priory in the 1920s.

Sources:

See also: Folkestone (temporary station), Folkestone East, Folkestone Harbour, Folkestone Warren Halt, Shakespeare Cliff Halt, Archcliffe Junction Staff Halt, Dover Town, Dover Admiralty Pier, Dover Prince of Wales Pier,

& Dover Harbour

See also:

Detailed history of Shakespeare Colliery with many photos.

Detailed history of the first Channel Tunnel attempt in 1880

Dover Marine Gallery 1: 1911 - April 1914

|

old6.jpg)

marine_old14.jpg)

marine_old22.jpg)

Dover Harbour, which is generally acknowledged to be one of the greatest feats of port construction at that time, was completed in 1909. The walls and piers were built of large blocks weighing from 30 to 40 tons. These blocks were made of concrete, with a granite facing to those that were to be placed on the outside surfaces of the walls above water level. The completed harbour was opened on 14 October 1909 by H.R.H. the Prince of Wales, the future King George V. In 1909 work started on the new station to create an artificial platform for the new terminus alongside the north end of the Admiralty Pier.

Dover Harbour, which is generally acknowledged to be one of the greatest feats of port construction at that time, was completed in 1909. The walls and piers were built of large blocks weighing from 30 to 40 tons. These blocks were made of concrete, with a granite facing to those that were to be placed on the outside surfaces of the walls above water level. The completed harbour was opened on 14 October 1909 by H.R.H. the Prince of Wales, the future King George V. In 1909 work started on the new station to create an artificial platform for the new terminus alongside the north end of the Admiralty Pier.

Repatriated British prisoners of war started to arrive at Dover on 17 November 1918. By February 1919 180 boats conveying 55,398 released former POWs were received by 130 trains. In January 1919 the large Customs Examination Shed in the station was utilised for the sorting out of demobilised men, who began to arrive at Dover. The number passing through Dover amounted to 720,664 servicemen. When the armistice came in November 1918, the SE&CR had a fine record of war service to its credit, and Field Marshall Sir Douglas Haig wrote the following letter of commendation to Cosmo Bonsor, the Chairman of the SE&CR Managing Committee: ‘The Army in France owes much to all connected with the control of our railway companies in the United Kingdom, and indeed in the Empire. They have at all times shown great willingness to help us in every possible way in their power. Track has been torn up to give us rails, engines, trucks, men, capable engineers, operations staff all have been sent abroad to us, regardless of their own special needs and demands of the people at home, and without a moment’s hesitation. But we have been more closely associated with the South Eastern & Chatham Railway than any other. The bulk of our ammunition and stores required for the maintenance of our armies, as well as several millions of men as reinforcements and on leave, have passed over their system. Their sphere of duty, too, has been nearest to the shores of France and Belgium, and consequently more open to hostile attacks by air and fear of invasion by sea. Undisturbed by any alarms the traffic for the Armies in France has never ceased to flow. This reflects the greatest credit on all concerned with the company’.

Repatriated British prisoners of war started to arrive at Dover on 17 November 1918. By February 1919 180 boats conveying 55,398 released former POWs were received by 130 trains. In January 1919 the large Customs Examination Shed in the station was utilised for the sorting out of demobilised men, who began to arrive at Dover. The number passing through Dover amounted to 720,664 servicemen. When the armistice came in November 1918, the SE&CR had a fine record of war service to its credit, and Field Marshall Sir Douglas Haig wrote the following letter of commendation to Cosmo Bonsor, the Chairman of the SE&CR Managing Committee: ‘The Army in France owes much to all connected with the control of our railway companies in the United Kingdom, and indeed in the Empire. They have at all times shown great willingness to help us in every possible way in their power. Track has been torn up to give us rails, engines, trucks, men, capable engineers, operations staff all have been sent abroad to us, regardless of their own special needs and demands of the people at home, and without a moment’s hesitation. But we have been more closely associated with the South Eastern & Chatham Railway than any other. The bulk of our ammunition and stores required for the maintenance of our armies, as well as several millions of men as reinforcements and on leave, have passed over their system. Their sphere of duty, too, has been nearest to the shores of France and Belgium, and consequently more open to hostile attacks by air and fear of invasion by sea. Undisturbed by any alarms the traffic for the Armies in France has never ceased to flow. This reflects the greatest credit on all concerned with the company’.  Much of the north end of Admiralty Pier was incorporated into an extensive network of trackwork and sidings around the new station; these were required to handle the large quantity of freight traffic passing through Dover during the war. Access to the station and sidings was controlled by a large 120-lever SE&CR-designed signal box on the down side approach to the station. The two platforms were spanned by a lattice footbridge at the north end of the trainshed.

Much of the north end of Admiralty Pier was incorporated into an extensive network of trackwork and sidings around the new station; these were required to handle the large quantity of freight traffic passing through Dover during the war. Access to the station and sidings was controlled by a large 120-lever SE&CR-designed signal box on the down side approach to the station. The two platforms were spanned by a lattice footbridge at the north end of the trainshed.  On each platform there were three large blocks of brick buildings, each 100ft in length and 25ft in width. These buildings were allocated to a variety of purposes, including waiting rooms, tea rooms, dining and refreshment facilities, post and parcel shed railway staff rooms etc. At the end of each platform nearest to the Admiralty Pier provision was made for a Post Office, and at the end of the other platform there was a Customs Examination and Clearance Shed.

On each platform there were three large blocks of brick buildings, each 100ft in length and 25ft in width. These buildings were allocated to a variety of purposes, including waiting rooms, tea rooms, dining and refreshment facilities, post and parcel shed railway staff rooms etc. At the end of each platform nearest to the Admiralty Pier provision was made for a Post Office, and at the end of the other platform there was a Customs Examination and Clearance Shed.  On 14 November 1924 the 'Continental Express' boat train was introduced and consisted of the six first class Pullman cars, a baggage and brake van. It left London Victoria at 10.50 am, the return 'Continental Express' train leaving Dover for London at 5.30 pm.

On 14 November 1924 the 'Continental Express' boat train was introduced and consisted of the six first class Pullman cars, a baggage and brake van. It left London Victoria at 10.50 am, the return 'Continental Express' train leaving Dover for London at 5.30 pm.

The ‘Canterbury’ was launched on 13 December 1928 at Dumbarton and arrived in Dover on 30 April 1929, commencing service on 15 May, the same day as the ‘Golden Arrow’. The journey between London and Paris was advertised to take 6½ hours and each day the ‘Golden Arrow’ was scheduled to depart London Victoria at 11.00 am and reach Dover Marine station at 12.38 pm. As the line is fairly level with a very long straight section, speeds of 60 mph were not unknown. Having crossed the Channel in the ‘Canterbury’ and on reaching Calais the passengers were transferred to the awaiting ‘Flèche d’Or’, a four-cylinder Nord Pacific of the French Northern railway, arriving in Paris at 5.35pm UK time. The single fare was £6.10s.

The ‘Canterbury’ was launched on 13 December 1928 at Dumbarton and arrived in Dover on 30 April 1929, commencing service on 15 May, the same day as the ‘Golden Arrow’. The journey between London and Paris was advertised to take 6½ hours and each day the ‘Golden Arrow’ was scheduled to depart London Victoria at 11.00 am and reach Dover Marine station at 12.38 pm. As the line is fairly level with a very long straight section, speeds of 60 mph were not unknown. Having crossed the Channel in the ‘Canterbury’ and on reaching Calais the passengers were transferred to the awaiting ‘Flèche d’Or’, a four-cylinder Nord Pacific of the French Northern railway, arriving in Paris at 5.35pm UK time. The single fare was £6.10s. The specifications, drawn up by George Elson, Chief Engineer of Southern Railway, were a concrete dock 414ft long and 72ft wide, with a minimum depth of water of 17ft to a maximum of 36ft. Construction work started in August 1933 and two railway lines were laid to connect the dock to the main line into Dover Marine. The Southern Railway commissioned three purpose built ferries from Swan, Hunter & Wigham Richardson of Newcastle upon Tyne. Each ship was designed to take 12 sleeping cars, 500 passengers during the day, or approximately 40 goods wagons. There was also a small floor above the train deck to accommodate approximately 20 cars.

The specifications, drawn up by George Elson, Chief Engineer of Southern Railway, were a concrete dock 414ft long and 72ft wide, with a minimum depth of water of 17ft to a maximum of 36ft. Construction work started in August 1933 and two railway lines were laid to connect the dock to the main line into Dover Marine. The Southern Railway commissioned three purpose built ferries from Swan, Hunter & Wigham Richardson of Newcastle upon Tyne. Each ship was designed to take 12 sleeping cars, 500 passengers during the day, or approximately 40 goods wagons. There was also a small floor above the train deck to accommodate approximately 20 cars. On 14 January 1939 Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax travelled by way of Dover Marine, using the ‘Golden Arrow’ and the ‘Canterbury’, for Rome. This was to meet with Benito Mussolini, Italian Prime Minister and leader of the National Fascist Party, in an effort to persuade him not to become involved in the pending conflict. World War II was declared on 3 September 1939. Following the ‘Golden Arrow’s’ last trip, the ‘Canterbury’ left Dover for conversion into a troop carrying ship. The ship ‘Invicta’ was built in 1939 to take over from the ‘Canterbury’ but she was also commandeered for war work following her launch in 1940.

On 14 January 1939 Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax travelled by way of Dover Marine, using the ‘Golden Arrow’ and the ‘Canterbury’, for Rome. This was to meet with Benito Mussolini, Italian Prime Minister and leader of the National Fascist Party, in an effort to persuade him not to become involved in the pending conflict. World War II was declared on 3 September 1939. Following the ‘Golden Arrow’s’ last trip, the ‘Canterbury’ left Dover for conversion into a troop carrying ship. The ship ‘Invicta’ was built in 1939 to take over from the ‘Canterbury’ but she was also commandeered for war work following her launch in 1940.

To accommodate 12-car multiple-unit trains when the electrification from London via, Faversham started in June 1959, the two island platforms at Dover Marine were extended by 114ft, with 24ft ramps. The extensions comprised prefabricated concrete components, manufactured at Exmouth Junction concrete works. This necessitated altering the layout of the tracks at the London end and the construction of a riveted steel footbridge across the approach tracks from Dover Priory, linking the main entrance beside the ‘Lord Warden’ hotel with the Customs Hall, on the northern perimeter of the Western Docks. The bridge ran from the landing at the top of the stairs from the street entrance opposite the hotel.

To accommodate 12-car multiple-unit trains when the electrification from London via, Faversham started in June 1959, the two island platforms at Dover Marine were extended by 114ft, with 24ft ramps. The extensions comprised prefabricated concrete components, manufactured at Exmouth Junction concrete works. This necessitated altering the layout of the tracks at the London end and the construction of a riveted steel footbridge across the approach tracks from Dover Priory, linking the main entrance beside the ‘Lord Warden’ hotel with the Customs Hall, on the northern perimeter of the Western Docks. The bridge ran from the landing at the top of the stairs from the street entrance opposite the hotel.

Dover Marine was renamed Dover Western Docks on 14 May 1979, and although its future seemed secure the ‘Night Ferry’ was withdrawn on 31 October 1980. By this time the carriages were outdated and in need of replacement; they were not air conditioned, and during the ship voyage, while inside the ship, they became notably hot in summertime. This was exacerbated by the chaining of the vehicles to the ship's deck, an activity underneath the sleeping compartments which inevitably woke most passengers during the middle of the night. The carriages were over 40 years old and, by some margin, were the oldest passenger vehicles running on the British network.

Dover Marine was renamed Dover Western Docks on 14 May 1979, and although its future seemed secure the ‘Night Ferry’ was withdrawn on 31 October 1980. By this time the carriages were outdated and in need of replacement; they were not air conditioned, and during the ship voyage, while inside the ship, they became notably hot in summertime. This was exacerbated by the chaining of the vehicles to the ship's deck, an activity underneath the sleeping compartments which inevitably woke most passengers during the middle of the night. The carriages were over 40 years old and, by some margin, were the oldest passenger vehicles running on the British network.

Demolition and track-lifting commenced at the beginning of 1996. The Dover Harbour Board had hoped to demolish everything to build a new cruise terminal but the trainshed and the entrance building on Lord Warden Square were Grade II listed by English Heritage on 22 June 1989 so the only demolition related to the platform extensions that had been added in 1959.

Demolition and track-lifting commenced at the beginning of 1996. The Dover Harbour Board had hoped to demolish everything to build a new cruise terminal but the trainshed and the entrance building on Lord Warden Square were Grade II listed by English Heritage on 22 June 1989 so the only demolition related to the platform extensions that had been added in 1959.

marine_old38.jpg)

Home

Page

Home

Page