ROYAL ORDNANCE FACTORY 8 - THORP ARCHBACKGROUND Following the end of WW1, a review of the armaments industry resulted in the closure of nearly all of the ammunition provision facilities, retaining just the Royal Arsenal, Woolwich, the Royal Gunpowder Factory, Waltham Abbey and the Royal Small Arms Factory, Enfield which would satisfy post-war needs. In addition the National Filling Factory at Hereford was retained on a care and maintenance basis as a reserve, should it be needed. This site was reactivated in WW2 to become Filling Factory No.4-Hereford. The Royal Arsenal at Woolwich was unique, being an explosives factory, a filling factory, an engineering factory, a gun foundry, a proofing range and storage magazine all on the same huge site, which together with the two other London sites constituted a major bombing target in the event of war. EARLY PLANNING The majority of the ROFs were built in the re-armament period just before and just after the start of WW2 in areas regarded as 'relatively safe', which until 1940, meant from Bristol in the south and then west of a line that ran from (roughly) Weston-super-Mare in Somerset northwards to Haltwhistle, Northumberland, and then north-westwards to Linlithgow in Scotland. The South, South East and East of England were regarded as 'dangerous' and the Midlands area, including Birmingham, as 'unsafe'; however this constraint was overcome by the necessity to site factories to where workers were available to staff them.  Woolwich was, however, poorly sited and was especially vulnerable to an air attack. With the rise of the Nazi party in Germany culminating in Adolf Hitler being confirmed as Führer (leader) of Germany on 19 August 1934 another war with Germany seemed inevitable. On 3 December 1934, a decision was taken to close the explosives production and filling facility at Woolwich and build a new factory at a more secure location. The site chosen was Chorley in Lancashire, and construction began there in 1937 with some small-scale production underway in 1938. Before construction had even started, it was clear that it would be impossible to determine the precise demand for ammunition before war had even been declared so construction of a second large factory at Bridgend was also felt necessary to supplement Chorley. Construction started here in March 1938 but production did not start until March 1940, six months after the declaration of war with Germany. With the proposed demise of Woolwich the Navy made it clear that they would also require a dedicated filling factory. A site at Glascoed, near Pontypool in South Wales, was selected with the intention that it would work in conjunction with Bridgend. Construction started here in February 1938 with production also starting in March 1940. These are the only sites where construction started before the outbreak of war although in 1936 there had been discussion about an additional site to satisfy the needs of the RAF. The three factories already under construction were considered sufficient to supply the needs of all three services with Woolwich being retained as back up, followed by the reactivated No.4 Filling Factory at Hereford. All the multiple functions at Woolwich with the exception of explosives production and limited filling were retained throughout WW2 and beyond..

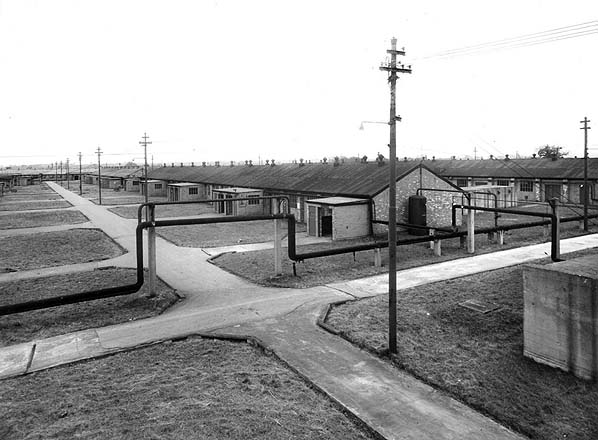

Some of the Group 5 buildings looking south. By the time this photo was taken in the mid-1950s the 'cleanways' between the buildings were no longer maintained to the spotless condition that was required during WW2. Where they crossed the lagged pipes carrying steam around the factory, and also the pipes of the compressed air ring, these were carried above the ‘cleanways’. An air reservoir tank is seen on the right. In 1938, while construction of the three factories was underway, the government reviewed the situation as war was rapidly approaching. It was clear that the projected production capacity would be inadequate as the army increased to ten divisions, and the needs of the RAF were also reassessed. In May 1939 government approval was given for at least two additional factories; one of these was to be at Swynnerton near Stafford. Before the site of the sixth factory could be decided war was declared on 3 September 1939. Five days later the sites for two more factories were chosen at Risley and Kirkby, both in Lancashire. Construction of both started within a few weeks. The eight factories now under construction were expected to be sufficient to supply an army of up to 20 divisions. Five months into the war the government once again reassessed the need for ammunition to support an army that was expected to increase in size to 32 divisions. It was clear that additional factories would soon be required. Three sites in Yorkshire had been considered at a meeting on 24 January 1940 with the most suitable being Thorp Arch between Leeds and York. The main criteria for its selection were good rail connections and the availability of labour, which could be brought in by train from Leeds, Bradford, Wakefield and Normanton. At the end of February 1940 the war cabinet approved the construction of No.8 Filling Factory at Thorp Arch and No.9 at Aycliffe in Durham. Construction was underway on 18 May 1940. This was not to be the end of the programme; by the close of war 44 factories had been built, many for specific types of ammunition or purposes. The largest filling factories covered an area of up to 1,200 acres.

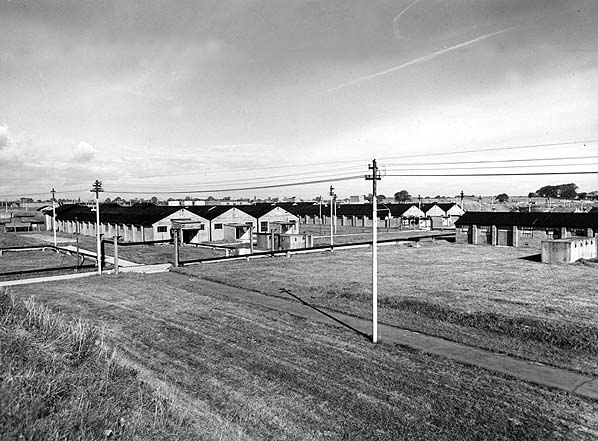

Group 5 looking north towards the larger buildings adjacent to Avenue C (West).  Aerial view of ROF Thorp Arch in 1946. The exchange sidings and carriage sidings are seen on the left. Thorp Arch station is seen north-west from the sidings. Click to enlarge. CONSTRUCTION IS UNDERWAY AT THORP ARCH

Initially construction workers also arrived at Thorp Arch station but the small station was unable to cope with several hundred workers arriving each morning. Although this put a strain on the few station staff it appeared not to trouble the workers who were content to jump from long trains directly onto the track. In June 1941 the platforms were lengthened to accommodate the long workmen's trains, but it was soon apparent that they were still inadequate and that more suitable facilities would soon be required, especially when the factory went into production with a much larger workforce.

Two hostels, each capable of taking 1,000 workers were built at Wetherby, but with an expected workforce of 18,000 these would do little to relieve the problem as the bulk of the workforce, mainly women, would be arriving and departing by train each day. The LNER provided the solution by proposing a circular railway running round the perimeter of the site. The single-track line would be provided with automatic signalling which would allow trains to follow each other in quick succession. Carriage sidings would also be built to allow the trains to be stabled on site after dropping off the workers. They could wait in the sidings until they were needed to collect workers after the off-going shift. Four workers’ platforms were proposed which would allow them do disembark close to their actual place of work. Construction started immediately with two of the factory platforms being brought into use on 20 November 1941 and the other two platforms used on completion of the circular railway on 19 April 1942.  Group 10 included the engineering workshops for the factory. The machine shops shown here are the largest buildings in the factory. These workshops were served by Walton Platform on the circular railway.  The structural shop handled mainly repairs to the structures within the factory. The factory was divided into 'clean' and 'dirty' areas. Workshops where the actual filling and most of the other procedures involved in producing the final shell took place were ‘clean’ areas. These could only be reached by passing through a 'shifting house' where all personnel changed into protective clothing and shoes. ‘Dirty’ areas were generally stores or magazines served by railway sidings; these handled the incoming materials and components or finished munitions ready for dispatching. The factory was also divided into a number of different areas or groups of buildings performing specific functions: Group 1: Buildings in this group handled and manufactured the most delicate explosives. One of the primary functions of this group was to fill caps and detonators. Group 2: Buildings here handled powdered TNT and Tetryl, a sensitive explosive compound used to make detonators and explosive booster charges. The function of this group was the production of fuse magazine pellets, exploder pellets and exploder bags.

Group 3: Fuses were assembled and filled in this group using the detonators that were produced in Group 1 and the magazine pellets from Group 2. In military munitions, a fuse is the part of the device that initiates ignition. Group 4: Specific blends of gunpowder for use in the delay mechanisms of time fuses were produced here. Group 5: Buildings here were involved with the filling of cartridges which could then be sent to the magazines awaiting dispatch. The processes included filling cloth bags with cordite, for breech loading ammunition; filling cordite into brass cartridge cases for individually-loaded ammunition; filling cordite into brass cartridge cases; and assembly of those cases to filled shells, for issue as a complete round, was also carried out here. Group 6: Buildings here made smoke-producing compounds for use in smoke shells. Tracer ammunition for marking targets was also produced here. Group 7: Filled small arms ammunition. Group 8: All the heavy work was carried out in the buildings of this group including the mixing of high explosives for filling large shells and bombs. Group 9: This group contained all the large storage magazines for completed shells awaiting dispatch. Many of these magazines were covered with soil and surrounded by an earth bund, and each was served by a rail siding from the perimeter railway. Group 10: Test ranges and proof yards where a percentage of each batch would be tested.

MUNITIONS PRODUCTION STARTS   The Thorp Arch ladies with their presents for Adolf.  One of the Group 8 magazines on the north side of Road 7 in April 2013. The magazine is of brick construction with a thin roof surrounded by a substantial earth bund. In the event of the magazine exploding all the debris should go upwards and not damage adjacent buildings. The magazine is connected by a short siding to the main railway network. Although the site was sold in 1959 for redevelopment as an industrial estate. not all of the buildings have been reused or demolished. This is one of the few sections of the internal rail network to survive. Photo by Nick Catford Within the factory there was a huge network of internal roads and railway sidings. There were also 'cleanways’ which were special roads for taking components between buildings. They were made of gritless asphalt coated with a shellac-like material, and were kept spotless at all times by constant sweeping and washing.

The first 20mm ammunition was produced at Thorp Arch on 8 February 1952, and production increased rapidly with 13,263,000 rounds being turned out in the first twelve months. Once the factory was in full production it was able to produce 500,000 rounds a week in a single shift. Gradually other areas of the factory, including proof yards and ranges, bulk magazines, laundry, components shops, and clothing distribution, were also provided to meet the factory production requirements. Unlike during WW2 the workforce was mainly male, although when the requirement for exploders (detonators) increased it was necessary to start a night shift which was initially worked by women, although the factory eventually adopted all-male night working. By the middle of 1953 the demand for 20mm ammunition was in decline and production switched to the production of high explosive fuses. Other areas of the factory were renovated for the production of rockets, which started in June 1953, and 1,000 lb bombs which started in October 1953. As other forms of ammunition were required more areas of the former factory were renovated and brought back on line.

AFTER CLOSURE Many of the original buildings still survive and have been put to new uses. while some remain in a derelict state awaiting renovation and reuse or demolition. Sources:

See also Thorp Arch station and platforms on the Thorp Arch Railway: River Platform, Ranges Platform, Roman Road Platform & Walton Platform

|

arch17)2.jpg)

Home Page

Home Page