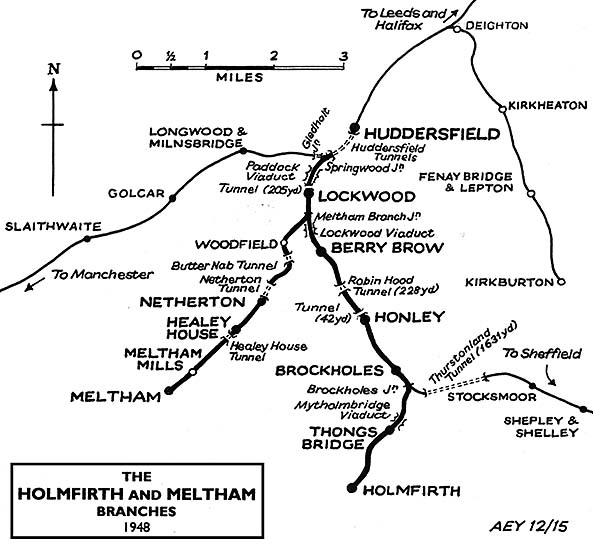

HOLMFIRTH BRANCH - BRIEF HISTORY[Source: Alan Young]

Parliamentary approval for the Huddersfield & Sheffield Joint Railway (H&SJ) was obtained on 30 June 1845 for the 13-mile route from Huddersfield to Penistone. The H&SJ Brockholes to Holmfirth branch was included in this Act. John Hawkshaw was appointed Chief Engineer to the project which tested his skill as the line cut across the grain of the country. Messrs Miller, Blackie and Shortridge secured the contract for building both the ‘main line’ and the Holmfirth Branch. The double-track main line wound its way through the hilly Pennine landscape, with deep valleys and tall ridges athwart its path. Six tunnels, totalling 3,427yd were required, together with deep cuttings, tall embankments, 57 bridges and four major viaducts. Nowhere else in Britain illustrates more clearly than the West Riding Sheeran’s (1994) assertion that ‘railway engineers were to make the viaduct their trademark, building them across fertile valleys, barren moorlands or crowded cities’.

Immediately on leaving Huddersfield station the line (shared with the LNWR) plunges underground, and emerges into daylight at Springwood Junction. The original intention was for the Penistone line to leave the Stalybridge and Manchester line inside the existing tunnel, but Parliament refused permission for this arrangement on the grounds of safety; as a result the tunnel was opened out and Springwood cutting was created. Immediately south-west of Springwood Junction the Manchester line enters a tunnel, whilst the H&SJ line heads south to be carried 70ft above the River Colne on Paddock Viaduct, with its six stone spans and four central wrought iron lattice girders that carry the line over the River Colne and the highway.

Following Lockwood Tunnel (205yd) and station follows the spectacular Lockwood Viaduct, constructed of the sandstone hewn from the two cuttings immediately south – some 201,950 cu yd were excavated. The viaduct stretches 476yd, with 32 semi-circular arches as well as an oblique arch over Meltham Road and a further arch over another road at the southern end. The structure stands 122ft above the River Holme. Further on are Robin Hood (228yd) and Honley (42yd) tunnels; both of these were planned to be cuttings.

After Brockholes, where the Holmfirth Branch diverged, are Thurstonland Tunnel (1,631yd) and Cumberworth Tunnel (906yd). At Denby Dale a substantial timber trestle viaduct was built, apparently prompted by a strike among the stonemasons. Even before the line opened this structure was severely damaged in a gale on 27 January 1847 when half of the supports were blown down; this incident confirmed local people’s fears that a similar structure being built at Mytholmbridge on the Holmfirth Branch might not be safe. A stone structure was later provided at Denby Dale. Beyond this viaduct the main line passed through Wellhouse Tunnel (415yd), followed by another spectacular viaduct, immediately north of Penistone station; this one is 367yd in length with 29 arches and it stands 98ft above the River Don. At Penistone the line from Huddersfield met the Manchester, Sheffield & Lincolnshire Railway (MS&L) which had opened in 1845 and provided the remainder of the route through Deepcar to Sheffield. In July 1846 the Huddersfield & Sheffield Joint Railway amalgamated with the Manchester & Leeds Railway, the company being renamed the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway (LYR) in 1847.

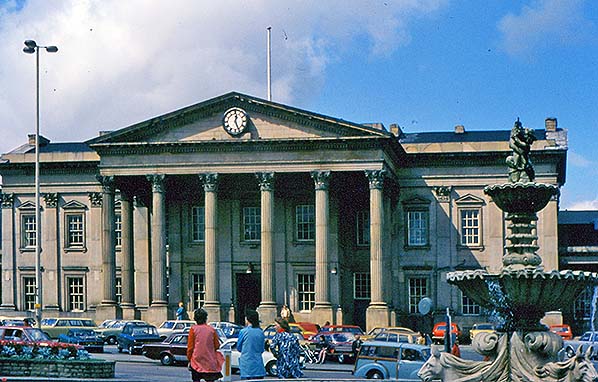

At the northern end of the route from Huddersfield to Sheffield was a remarkable station which, thankfully, is still with us. In comparison to neighbouring Leeds and Bradford, Huddersfield was a relatively small town, yet its station was ‘the finest railway building in the region, and one of the outstanding railway monuments in the whole country’ (Sheeran 1994). Sir John Betjeman went even further, praising Huddersfield as possessing ‘the most splendid station façade in England’. The reason for its magnificence was the influence of the Ramsden family who owned much of Huddersfield and were in a position to control developments in the town. At first the trustees of the family opposed railway construction through the town, principally because of the family’s interests in the Ramsden (or Huddersfield Broad) Canal which connected the town and its industry to the Calder & Hebble Navigation. However, they eventually realised that a railway might bring them advantages, and the Earl Fitzwilliam, one of the trustees, appears to have been able to select the architect (James Piggott Pritchett of York) and thereby influence the design of the station. The style was classical, having a central two-storey block behind a huge portico with a triangular pediment supported on Corinthian columns; the side gables of the central block were also finished with triangular pediments. On either side of this block, colonnades connected it to a tall single-storey pavilion, each with a colonnaded portico. The station was completed in 1850, but its design was of a style that was already falling out of favour as the tradition of neoclassical public buildings drew to a close; Sheeran notes that it was amongst the last achievements of the neoclassical movement. Originally the pavilions accommodated the booking offices for the companies that used the station – the LYR and LNWR – but today passengers can enter the central booking hall via the flight of steps beneath the main portico. It seems incredible that in the 1960s-70s there was talk of replacing this fine structure with something more functional, but its Grade I listing will ensure its long-term survival.

Work began on building the Huddersfield – Penistone line in August 1845 with the intention of opening it with the Holmfirth Branch in 1848, but construction of some sections was delayed by protracted negotiations to purchase some of the land that the railway required; moreover, the Paddock and Lockwood viaducts took longer than expected to complete. The opening date was adjusted to 24 June 1850, deferred again until 1 July 1850. On the ‘main line’ services were disrupted in 1916 when part of the Penistone Viaduct collapsed spectacularly as a result, it is thought, of the foundations being affected by heavy rain. An engine that had just arrived with a train from Huddersfield was running round the train to be coupled up for the return journey when the viaduct arches failed, and it plunged into the valley below’ ending up on its side. Within months the viaduct was repaired allowing the line to reopen.

The Huddersfield – Penistone route was proposed for closure in the ‘Beeching Report’ of 1963, and thankfully it survived long enough to be reprieved on 14 April 1966 by Minister of Transport, Barbara Castle, as one of the commuter routes whose closure would place an intolerable burden on the local roads and were considered worth subsidising; only Berry Brow station received consent to closure. Thomas (2007) notes: ‘the number of commuters using the line from some of the rural statons was not large and made the Minister’s decision surprising but, of course, welcome’.

As an economy measure the section of route between Clayton West Junction and Penistone was reduced to single track in November 1969. The route was threatened again in the late 1970s / early 1980s as the neighbouring West and South Yorkshire authorities were unable to make a co-operative decision on continuing subsidies, with the absurd situation that at different times the West Yorkshire section, Huddersfield-Denby Dale, and Denby Dale-Sheffield (South Yorkshire’s responsibility) were proposed for closure. This absurd state of affairs is chronicled by Martin Bairstow (1993). Eventually the route between Penistone and Sheffield - whose only surviving station was Wadsley Bridge, kept open for occasional football special trains – was closed, and services were diverted via a reopened line to Barnsley, on which there are stations serving Silkstone Common and Dodworth. The result was a slower journey but Barnsley’s rail connectivity was improved, and Meadowhall station, serving the Meadowhall shopping centre, opened on the line in 1990, providing an attractive destination for residents living along the railway from Huddersfield. The northern part of the route from Springwood Junction (Huddersfield) through Brockholes to Stocksmoor was singled in 1989, leaving a double-track section from Stocksmoor to Clayton West Junction. The ‘Penistone Line’ has experienced a great increase in traffic in the present century, not least because of the enterprise of the Penistone Line Partnership whose evening Music Trains, Burns Night specials and other attractions have brought publicity and passengers to the route.

THE BRANCH

The principal engineering structure on the short branch to Holmfirth was Mytholmbridge Viaduct over the New Mill Dyke Valley, almost ¾-mile beyond the junction. Originally intended to be stone-built, the decision was taken to save money by constructing it of timber; perhaps the stonemasons’ strike which influenced the H&SJ’s decision to use timber rather than stone for Denby Dale Viaduct was a consideration here too. Mytholmbridge Viaduct consisted of 26 bays, each 26ft 6in, with a maximum altitude of 86ft 6in to rail level, and it was built on a curve of 20 chains radius. Despite the disaster in January 1847 when part of the timber Denby Dale Viaduct was blown down in a gale, work went ahead with the timber structure at Mytholmbridge, only for most of this structure to collapse in a storm on 19 February 1849, as it was nearing completion. The Leeds Intelligencer (24 February 1849) reported that because the workmen were on their lunch break when the gale sprung up and destroyed three-quarters of the viaduct there were no casualties. Dismissing local people’s lack of confidence in this type of structure, the H&SJ rebuilt Mytholmbridge Viaduct in timber, and the line was ready for opening by the end of June 1850. The Holmfirth Branch had a falling gradient of 1 in 100 from Brockholes Junction to Thongs Bridge followed by an upward 1 in 120 gradient to Holmfirth, the terminus being at an altitude of 518ft. Amid great celebrations the Holmfirth Branch opened on 1 July 1850, with its one intermediate station at Thongs Bridge together with the line with which it connected at Brockholes. Church bells rang from the early morning, and almost all of the district’s population braved the rain to give the first train from Holmfirth with its party of guests a rousing send-off to Huddersfield at 11.25am. A band welcomed the train at Huddersfield station, and entertained the passengers as they alighted there and boarded a train for Penistone. Plans went awry later in the day when this heavily loaded train proved too much for the engine which skidded to a halt on the wet rails inside Thurstonland Tunnel, a short way beyond Brockholes. Half of the train was all that the locomotive could take forward to Stocksmoor so the remaining coaches had to wait in the tunnel for rescue. Such was the popularity of the new railway that in the first week Holmfirth station sold 1,869 tickets and Thongs Bridge 674. Earnshaw (1992) describes a curiosity of the branch in its earliest weeks when passengers complained about the poor timing of trains and missed connections. The reason was that Holmfirth parish church clock was 15 minutes slow; a letter in the local newspaper brought this discrepancy between ‘ecclesiastical time’ and ‘railway time’ to light. The former was changed to correspond to the latter! At first the branch had a shuttle service hauled by an engine based at Holmfirth shed and passengers changed at Brockholes. The need to change trains did not meet with the passengers’ approval. Thomas Normington, a long-term employee of the LYR who worked as a guard on the Holmfirth trains, overheard the Superintendent of the Line opining that it was not possible, on such a complicated line, to make a timetable to please the public and that he would give a £5 note to anyone who could produce one. Normington produced one in only a few days that not only met the public’s requirements but reduced working expenses by dispensing with the engine stabled at Holmfirth. His solution was to diagram through trains between Bradford and Holmfirth so as to eliminate the turn-round times at Huddersfield and Brockholes. The company adopted the idea – but Normington never received the £5! This matter is described by Normington in his book The Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway (see bibliography). He also gives a lively account of an incident in August 1852 when he was guard on the return journey of a 25-carriage Holmfirth - Hull excursion in which his heavily-loaded returning train ground to a halt in at midnight between Thongs Bridge and Holmfirth. Click here to read Normington’s account of the incident. February 1863 Bradshaw showed seven weekday and three Sunday departures for Huddersfield and the same frequency of arrivals.

The Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway (the owning company from 1847) realised that Mytholmbridge Viaduct would need to be replaced with a masonry structure, and on 13 July 1864 a tender of £7,100, submitted by Henry Wadsworth, was accepted to build a new viaduct in stone. It would consist of 13 arches, two of them of 29ft span and the others 37ft 8in. By 13 September 1865 all of the arches had been turned; new stonework was erected on the inside of the curve, and stone piers were between the timber uprights of the original trestle viaduct. The outer track on the trestle (the line to Holmfirth) remained in use and the inner half of the timberwork was dismantled as progress was made with the stonework. Unfortunately cracks appeared in the seventh pier from the Huddersfield end and three buttresses were built to support it. Tracks were laid on the completed half of the stone viaduct in preparation for running trains. The second Mytholmbridge Viaduct disaster occurred early in the morning, on Sunday 3 December 1865. A local miller (William England) heard a sound that he described as ‘like a clap! clap! clap! – one arch falling against another, regular and right furious, and the valley was filled with lime and smoke’. The entire stone viaduct had collapsed taking with it what remained of the timber structure. Mr England had the presence of mind to hurry to Brockholes station to raise the alarm, knowing that a train was due from Huddersfield shortly before 7.00am. However at Holmfirth passengers waiting in the cold for the 7.15am for Huddersfield were not aware of the cause of the delay until news reached them at 8.00am. Marshall (1969) – from whose book this report has been taken, based in turn on a report in Huddersfield Chronicle of 9 December 1865 – wonders why Holmfirth people were so keen to catch a train from the town so early on a winter Sunday morning. The investigation into the cause of the collapse reported that the seventh pier, in which the cracks had been seen, was built partly on rock and partly on gravel and so had slipped out of place; bad workmanship was also blamed. The report recommended that an embankment to replace the viaduct would be cheaper and quicker to build than another viaduct. However there was difficulty in obtaining the extra land required for an embankment, and so a viaduct was constructed, this time by contractors Gilbert & Sharp of Salford for £9,000.

The collapse of the viaduct left Holmfirth and Thongs Bridge stations cut off from the rest of the railway network. On 15 December 1865 the Manchester Carriage Co was hired to provide horse omnibuses between Holmfirth and Honley (the next station north of Brockholes) at £1.0.0 for the double journey; the LYR was to pay the tolls and supply conductors. Four railway carriages were stranded at Holmfirth station and, although the possibility was considered of bringing in an engine to work them as far as the gap, the LYR had them removed by road. Click here to read Thomas Normington’s account of the Mytholmbridge Viaduct collapse and how he made arrangements for providing a ‘rail replacement bus service’ for Holmfirth and Thongs Bridge. On 11 March 1867, braving a blizzard, hundreds of people crowded onto Holmfirth station to welcome the first train that had travelled over the new stone viaduct. The viaduct seems to have caused no further problems. It survived until 1976, 11 years after the line was abandoned, when it was blown up – temporarily blocking the stream that flowed beneath it.

On the ‘main line’ at Denby Dale, the timber viaduct, built in 1847 to replace the original timber structure that blew down in a gale, was itself replaced with a stone viaduct in 1882. By December 1895 the frequency of trains on the Holmfirth Branch had increased considerably in comparison to February 1863: 15 trains departed on Monday-to-Friday and 16 on Saturday, destinations being Huddersfield, Halifax and Bradford (via Halifax, Clifton Road or Mirfield) and there were four Sunday departures. The Holmfirth Branch was well patronised, its trains regularly formed of three or more carriages; Earnshaw remarks that prior to World War I services were often so crowded that ticket collectors boarded evening trains at Thongs Bridge to relieve congestion at Holmfirth’s ticket barrier.

Most passenger trains were hauled by LYR 0-4-4Ts and 0-6-2Ts until about 1900 when Aspinall 2-4-2Ts were introduced. Early twentieth century goods traffic was generally hauled by LYR A-Class 0-6-0s and 0-8-0s, with coal the principal inbound traffic and woollen products dispatched. A woollen transhipment warehouse stood adjacent to the platform at Holmfirth station. Thomas (2007) notes that runaway accidents on the steeply graded Holmfirth Branch were few, and these were mainly at Brockholes Junction where Holmfirth passenger coaches were being ‘slipped’ to make connections with trains to or from other destinations. One curious runaway incident occurred at Holmfirth when a coach ran into a turntable pit and was damaged beyond repair. The LYR was absorbed by the LNW in January 1922, and in January 1923 the Holmfirth branch became part of the LMS. At this time train frequency had changed little from that in 1895. Although excursion trains from Holmfirth remained popular, buses were to lure formerly regular passengers away from the railway. The frequent train service was, nevertheless, maintained until World War 2. Fowler 2-6-4T locos damaged the turntable at Holmfirth, and late in 1938 it was dismantled and a run-round loop replaced it. Thereafter most trains worked tender-first to Holmfirth and smokebox-first to Brockholes. By June 1943 the passenger service had declined to seven departures on Monday-to-Friday, eight on Saturday and no Sunday trains. The first BR London Midland Region timetable of summer 1948 showed a slight reduction to six weekday departures. On 2 April 1950 in a BR regional boundary adjustment the branch was transferred to the North Eastern Region.

Use of the branch continued to decline, and the train service dwindled to only three departures on weekdays in the summer 1959 timetable: morning trains to Halifax Town and Huddersfield and an early evening train to Bradford Exchange. Three trains arrived, two from Huddersfield and one from Leeds City. On 1 August 1959 Holmfirth Express carried a report in its ‘Comments’ column that the British Transport Commission intended to withdraw passenger services from the branch. The reporter expressed no surprise at the news, having regard to the number of passengers it carried, but he noted that it provided ‘something of a bombshell’ at the recent meeting of Holmfirth Urban District Council (UDC)at which councillors first heard of the proposed closure. Members of the council voted for a motion that the Clerk should compile a list of arguments for the retention of the service and suggest a change from steam to diesel engines (which was actually BR’s intention for the Huddersfield-Penistone service). The opinion was expressed at the meeting that their objections would probably have little effect ‘in view of the closing of so many stations in different parts of the country in recent times’. Later in August a letter to Holmfirth Express by George Taylor highlighted the poor connections to more distant destinations from the branch and the refusal of a request for a through booking to Manchester. The correspondent supported the idea of diesel traction and suggested direct services alternately to Leeds and Bradford.

On 22 August the report was carried in Holmfirth Express of the UDC’s concern that BR appeared to be unaware that a 450-pupil secondary modern school had opened in January 1959 at Thongsbridge [sic] close to the station, and that by 1961 the school roll would rise to 1,000. Traffic censuses to assess the volume of passengers had been held on the weeks ending 13 July and 19 October 1958 during school holidays, and the council estimated that since the new school opened 40 to 50 scholars were using the 8.27am from Holmfirth to Thongsbridge, returning to Holmfirth on the 4.24pm. Councillors were also told that no account had been taken of journeys between intermediate stations, such as Thongsbridge and Lockwood. BR’s statement that substantial numbers of passengers travelled by road from Holmfirth and Thongsbridge to Huddersfield to join trains, as support of the assertion that people had no need of Holmfirth to Huddersfield trains, was dismissed by councillors as absurd: the only reason for this use of road transport was the inadequacy of train services from Holmfirth and Thongsbridge. The local council also raised the matter that Holmfirth Branch trains were carrying more passengers than at any time in the 1950s, despite the threadbare service. They noted that, with no service during the greater part of the day, there was no opportunity for people to spend part of the day in Huddersfield. A trial period of evening trains was suggested, with an increased frequency of daytime trains for a minimum period of 12 months, to assess the volume of demand: the council suggested that to say there was no need for a train service because such a service has not been available was just foolish. They also queried why the 6.05pm train did not call at Thongsbridge. Councillors opined that a regular and frequent diesel service would increase the use of the line, and that economies could be made by singling the track and operating on a ‘One Engine in Steam’ system. Various assumptions made by BR were challenged by Holmfirth UDC. The assertion by BR that parcels traffic at Holmfirth was a rich source of revenue and that this would continue as before was queried, given that this traffic was handled by passenger trains. BR’s assurance that ‘alternative facilities’ were available at Brockholes station for users of Holmfirth and Thongsbridge stations was dismissed: ‘No person knowing the district and the routes these services take would ever think of suggesting them as alternatives…’ To reach Brockholes from Holmfirth a bus journey to Honley or New Mill would be used, then another to Brockholes, and these buses were not timed to connect with trains. Specific reference was made to Huddersfield Joint Omnibus Committee (HJOC) services 35 and 36 which were only hourly and did not ‘touch’ the railway except at Holmfirth and took 43 minutes to Huddersfield as opposed to 20 to 25 minutes by rail. A cynical note was struck by a reminder that British Railways was a 50% partner in HJOC buses, and the suggestion that, with its own interest in HJOC, Huddersfield Corporation would be most unlikely to oppose the closure.

BR’s figures on costs and savings were also queried, particularly the economics of continued maintenance of Mytholmbridge Viaduct for a freight train-only service. The North-East Transport Users’ Consultative Committee (TUCC) met at York on 1 September 1959 to consider the Holmfirth closure; the Keighley & Worth Valley Branch was also on the agenda. On 5 September Holmfirth Express reported that a spokesman told the press, immediately after the TUCC meeting that their recommendation was for the Holmfirth Branch to close, enabling BR to save £7,439 per annum. However – and this rankled with the Express – the case of the Keighley & Worth Valley, losing £15,426, was to be sent back to the British Transport Commission for further discussion. Ironically, one week after the TUCC endorsed the closure proposal, Thongs Bridge station achieved the distinction of a 2nd Class award and the coveted £4.0.0 prize (one of 40 to be so honoured) in the BR North Eastern Region Station Gardens Competition. Holmfirth and Brockholes gained 3rd Class awards (and £3). It would be churlish to suggest that the lightness of the station staff duties at Thongs Bridge, given the infrequency of trains and limited number of passengers, enabled the garden to be well tended; since January 1959 the garden might have provided solace and sanity between the morning and afternoon invasions of the station by school children! Holmfirth UDC appealed the TUCC’s decision, but it was rejected on the grounds that the appeal largely repeated the original objections and no new evidence had been produced. Holmfirth Express (3 October 1959) reported that the TUCC was clear that the travelling public had not supported the Holmfirth Branch to make it a paying proposition. A local councillor announced that there was every chance that diesels would start to run to Holmfirth on 2 November, but that he did not know how long they would run for: it would depend on how well they were supported. He referred to a special works outing train a few days earlier that conveyed 500 people, and to a 400% increase in the use of branch trains in the past ten years. His optimism was unfounded; on 17 October the newspaper reported that Holmfirth and Thongsbridge would close to passengers at the end of the month but that parcels and freight would continue to be handled as before. An article on 31 October, with consummate timing, was entitled ‘Attempts to solve the traffic problem in Holmfirth’. The passenger service ended on 2 November 1959 when the formal winter timetable began – almost two months later than the intended date of publication owing to a national printing dispute which delayed its production. Erroneously the Holmfirth service appeared in the winter 1959-60 timetable book; the branch closure coincided with the introduction of diesel multiple units on the Huddersfield-Penistone line, and the three phantom Holmfirth branch trains in each direction were also shown as diesel-operated. This is as close as Holmfirth got to having a regular diesel passenger train service! There being no Sunday trains, Saturday 31 October was the last day of passenger services. Holmfirth Express reported the proceedings (7 November). ‘To the accompaniment of exploding fireworks, the last train steamed out of Holmfirth Railway Station last Saturday afternoon ….. members of the Huddersfield Railway Circle had travelled up from Huddersfield to return on the train, as well as members of the West Riding Branch of the Railway Correspondence & Travel Society. Others had made long journeys including one person from London. Train spotters and souvenir hunters were there, and there had been a big demand for old tickets during the day, such as penny tickets to Thongsbridge and penny tickets for dogs. On the platform was a display of photographs taken by Leading Porter Herbert Jessop during his 37 years’ service at the station. There were further demonstrations at Thongsbridge where other passengers joined the train for a last ride to Huddersfield. So ends the history of the passenger service to Holmfirth which opened on 1 July 1850 with great rejoicing, including the ringing of Holmfirth church bells. Perhaps it would have been appropriate to ring a muffled peal on this occasion – but the bells are out of commission and there are no proficient ringers.’

After closure to passengers the Holmfirth Branch soldiered on for a few years handling only goods and parcels at Thongs Bridge and the terminus. The branch was singled in 1961 and Holmfirth signal box was decommissioned. At least three DMU excursions visited the branch after regular passenger services ended including an RCTS special in September 1964 and a school special to Wakefield in March 1965. The branch finally closed on 3 May 1965 and Holmfirth and Thongs Bridge stations ceased to handle goods traffic; Earnshaw notes that towards the end of April Type 4 diesel No.D259 ran trials along the branch and 8F No.48305 had the task of hauling away the remaining empty wagons. The rails were removed during 1966. The line’s principal engineering feature, Mytholmbridge Viaduct – having, unlike its predecessors, withstood Pennine gales for over a century - was demolished with explosives in 1976.

The buildings at Thongs Bridge station were demolished by the early 1970s but the platforms remained in place for some years longer and Holmfirth station stood derelict for many years. The office and waiting room range, together with the verandah remained in remarkably good repair when visited by the author in 1982; they were demolished and a place of worship and its car park were built on its site in 1985. The station building was restored for residential use. Parts of the trackbed of the Holmfirth Branch can be walked, albeit with some difficulty. From Station Road, Holmfirth, a steep, stony and overgrown path leads down to the River Holme; the original incoming line closely followed the course of the river and passed through Berry Bank Woods to Holmfirth. At the Brockholes end, and recently at Thongs Bridge, the course of the branch has been lost under a housing development. Sadly the tourists seeking a quaint ‘Summer Wine’ experience in Holmfirth, including horse-drawn tours of the town and afternoon tea in ‘Sid’s Café’, are denied the pleasure of arriving by train. How delightful a steam-hauled shuttle service from Brockholes would be! BIBLIOGRAPHY:

To see stations on the Holmfirth branch click on the station

|

aey.jpg) Penistone Viaduct, on the Huddersfield line immediately north of the station, is seen in April 1979. Photo from

Penistone Viaduct, on the Huddersfield line immediately north of the station, is seen in April 1979. Photo from .jpg) Lockwood Viaduct, looking north-east in 2001

Lockwood Viaduct, looking north-east in 2001 Lockwood station, the first after Huddersfield on the route to Brockholes and Penistone, looking north in the early years of the twentieth century. Today only the left (down) platform is in use, and the only original structure on it to survive is the shelter over the staircase rising to the down platform (on the extreme left). The 205yd Lockwood Tunnel is beyond the platforms

Lockwood station, the first after Huddersfield on the route to Brockholes and Penistone, looking north in the early years of the twentieth century. Today only the left (down) platform is in use, and the only original structure on it to survive is the shelter over the staircase rising to the down platform (on the extreme left). The 205yd Lockwood Tunnel is beyond the platforms The central section of the magnificent classical exterior of Huddersfield station in August 1974.

The central section of the magnificent classical exterior of Huddersfield station in August 1974. Huddersfield station looking south-west on 26 July 1984. The double-pitched trainshed is still a traditional feature of this splendid station at the time of writing (2016). The concrete lamp standards are of late LMS or early BR provenance; these, and the lampshades, are of unusual design. In the bay platform is a Class 141 ‘Pacer’ – a deservedly unpopular class of diesel multiple unit – in the West Yorkshire PTE livery. On the through line to the right is a Gloucester RC&W MPV (Motor Parcels Van). They were single unit vehicles and proved extremely useful, being fitted with two powerful (by DMU standards) engines to allow them to tow vans - which they frequently did. Class 128 MPVs sometimes ran coupled to other DMUs which were in passenger service in order to provide extra luggage/parcels capacity or simply for pathing reasons; the MPV here does appear to be coupled to another DMU

Huddersfield station looking south-west on 26 July 1984. The double-pitched trainshed is still a traditional feature of this splendid station at the time of writing (2016). The concrete lamp standards are of late LMS or early BR provenance; these, and the lampshades, are of unusual design. In the bay platform is a Class 141 ‘Pacer’ – a deservedly unpopular class of diesel multiple unit – in the West Yorkshire PTE livery. On the through line to the right is a Gloucester RC&W MPV (Motor Parcels Van). They were single unit vehicles and proved extremely useful, being fitted with two powerful (by DMU standards) engines to allow them to tow vans - which they frequently did. Class 128 MPVs sometimes ran coupled to other DMUs which were in passenger service in order to provide extra luggage/parcels capacity or simply for pathing reasons; the MPV here does appear to be coupled to another DMU.jpg) In 1916 part of the Penistone Viaduct collapsed spectacularly as a result, it is thought, of the foundations being affected by heavy rain. An engine that had just arrived with a train from Huddersfield was running round the train to be coupled up for the return journey when the viaduct arches failed, and it plunged into the valley below, ending up on its side. The loco, LYR 2-4-2T No.661, could not be recovered in one piece and so was scrapped on site; a replacement was built which

In 1916 part of the Penistone Viaduct collapsed spectacularly as a result, it is thought, of the foundations being affected by heavy rain. An engine that had just arrived with a train from Huddersfield was running round the train to be coupled up for the return journey when the viaduct arches failed, and it plunged into the valley below, ending up on its side. The loco, LYR 2-4-2T No.661, could not be recovered in one piece and so was scrapped on site; a replacement was built which On 30 October 1990 a ‘Pacer’ DMU is leaving Penistone station en route to Huddersfield

On 30 October 1990 a ‘Pacer’ DMU is leaving Penistone station en route to Huddersfield Looking south-east at Stocksmoor station on 2 July 1992 as a ‘Pacer’ DMU rattles off towards Shepley and Penistone. This is on the short section of the Huddersfield-Penistone line that retains double track at the present time.

Looking south-east at Stocksmoor station on 2 July 1992 as a ‘Pacer’ DMU rattles off towards Shepley and Penistone. This is on the short section of the Huddersfield-Penistone line that retains double track at the present time.

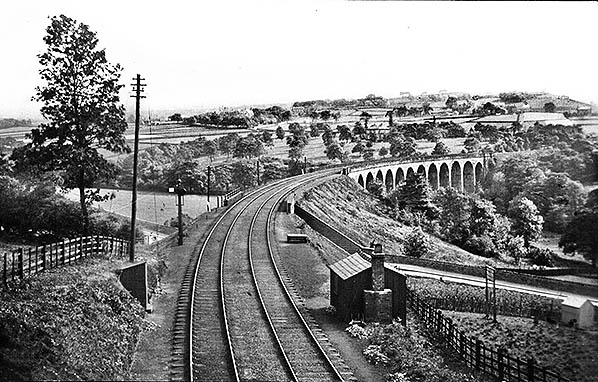

Mytholmbridge Viaduct, between Brockholes and Thongs Bridge, looking south.

Mytholmbridge Viaduct, between Brockholes and Thongs Bridge, looking south. On a Bank Holiday in 1897 towards the north-east end of Holmfirth station’s single platform some smartly-dressed gentlemen are posing nonchalantly for the cameraman. The stone building and substantial glazed awning are new, having been constructed only months before the photo was taken. The building ahead on the platform is the woollen transhipment warehouse. Various wagons can be seen on the goods sidings to the left.

On a Bank Holiday in 1897 towards the north-east end of Holmfirth station’s single platform some smartly-dressed gentlemen are posing nonchalantly for the cameraman. The stone building and substantial glazed awning are new, having been constructed only months before the photo was taken. The building ahead on the platform is the woollen transhipment warehouse. Various wagons can be seen on the goods sidings to the left. 1894 1:10560 OS map. Mytholmbridge Viaduct is seen to the north-east of Thongs Bridge station.

1894 1:10560 OS map. Mytholmbridge Viaduct is seen to the north-east of Thongs Bridge station. A three-coach branch passenger train is standing at Holmfirth station on Saturday 3 November 1956; this is most likely to be the 1.33pm departure. The Tudor Gothic station building and the platform verandah are clearly shown in the north-eastward view. The woollen ‘tranship’ shed beyond the verandah has been removed

A three-coach branch passenger train is standing at Holmfirth station on Saturday 3 November 1956; this is most likely to be the 1.33pm departure. The Tudor Gothic station building and the platform verandah are clearly shown in the north-eastward view. The woollen ‘tranship’ shed beyond the verandah has been removed The Brockholes up platform is seen in the 1950s/60s looking south-east from the down platform. Although the buildings are shown clearly it is the extraordinarily large LYR sign directing passengers to Huddersfield to use the bridge that catches the eye

The Brockholes up platform is seen in the 1950s/60s looking south-east from the down platform. Although the buildings are shown clearly it is the extraordinarily large LYR sign directing passengers to Huddersfield to use the bridge that catches the eye

All that remains of Mytholmbridge Viaduct after demolition in 1976.

All that remains of Mytholmbridge Viaduct after demolition in 1976.

Home Page

Home Page