Notes: On 12 June 1844 the GWR opened its line to Oxford from Didcot with a terminus south of the Thames on what was then open land. The location is now Western Road, Grandpont and the site of the inconvenient terminus was at this road's western end with the nearest landmark today being St Matthew's Church. The following year the Oxford & Rugby Railway (O&R) began construction of its line through and north of Oxford. The O&R formed a junction with the GWR at New Hinksey, the site of what was known as Millstream Junction being immediately north of what is today the bridge taking Old Abingdon Road over the railway. Through trains therefore were obliged to reverse in order to serve the original Oxford terminus. While still under construction the O&R was taken over by the GWR and the O&R opened to traffic as far as Banbury on 2 September 1850. The nuisance that had become the original terminus remained in use until 1 October 1852 when it was closed to passengers, becoming a goods depot until final closure on 26 November 1872 - the same day the broad gauge was abandoned between Didcot and Oxford. The 1852 closure of the original terminus coincided with the opening of the present Oxford Station which, following the arrival of the L&NWR at its Rewley Road station, was named Oxford General for many years.

The O&R had been built as a single track broad gauge line but was never to reach Rugby. By a complicated involvement with the Birmingham & Oxford Junction and the Birmingham Extension Railways the line forms the present day Didcot - Oxford - Birmingham line. The Rugby section was to have branched off at a junction close to Knightcote, just north of Fenny Compton and proceeded via Southam and Dunchurch to Rugby. Quite why this section was never built is not entirely clear although the gauge problem which would have presented itself at Rugby would seem the likely reason. While the GWR broad gauge is quite fascinating from the viewpoint of today, the nuisance that was Brunel's broad gauge could be said to be something of an understatement. In the event the broad gauge north of Oxford was abandoned on 1 April 1869 but by then any desire to reach Rugby had long since been abandoned.

1884 6" OS map shows Woodstockroad (Kidlington) station 6 years before the Woodstock branch opened.

1884 6" OS map shows Woodstockroad (Kidlington) station 6 years before the Woodstock branch opened.

Some five miles north of Oxford lies the village of Kidlington which today has spread westwards towards the railway but in the 19th century was one mile away across open countryside and of course the centre of the village still is. The history of a railway station in this locality can be quite confusing. Langford Lane station was opened in April 1855 adjacent to the road of that name and in July of the same year was renamed ‘Woodstock Road’. This caused a problem further north where there was a pre-existing station named ‘Woodstock,’ opened in 1850 and renamed ‘Woodstock Road’ the following year; this was renamed ‘Kirtlington’ but due to confusion with Kidlington, actual or perceived, which Langford Lane/Woodstock Road became in 1890 was renamed again to Bletchington (alternatively spelled Bletchingdon). Nothing is known about Langford Lane station other than its dates of operation under that name and that it would have had two platforms, as by 1855 the single track broad gauge line had been doubled; neither is it clear if what became Woodstock Road was a straightforward renaming, as it usually claimed, or a new station. Therefore and as can be seen there have been two stations named ‘Woodstock Road’, neither of which were anywhere near the town of Woodstock.

With the opening of the Woodstock branch, Woodstock Road, that is the former Langford Lane version, reputedly became ‘Kidlington for Blenheim’ on 19 May 1890 but photographic evidence exists showing that in or by the early 20th century the running-in boards announced ‘Kidlington change for Blenheim & Woodstock’ which by that time was rather more informative than simply ‘Kidlington for Blenheim’. It will be noticed that, including at the branch terminus, the name ‘Blenheim’ maintained some prominence. The usual layout of railway stations placed the station buildings, or at least the main buildings, on the side of the line closest to the town or village that the stations purported to serve even if the town or village was miles away which it quite often was. Kidlington was no exception and as a hark back to its ‘Woodstock Road’ days the buildings were on the west side of the line, closest side to the town of Woodstock some three miles away to the north-west as the proverbial crow flies.

With the opening of the Woodstock branch, Woodstock Road, that is the former Langford Lane version, reputedly became ‘Kidlington for Blenheim’ on 19 May 1890 but photographic evidence exists showing that in or by the early 20th century the running-in boards announced ‘Kidlington change for Blenheim & Woodstock’ which by that time was rather more informative than simply ‘Kidlington for Blenheim’. It will be noticed that, including at the branch terminus, the name ‘Blenheim’ maintained some prominence. The usual layout of railway stations placed the station buildings, or at least the main buildings, on the side of the line closest to the town or village that the stations purported to serve even if the town or village was miles away which it quite often was. Kidlington was no exception and as a hark back to its ‘Woodstock Road’ days the buildings were on the west side of the line, closest side to the town of Woodstock some three miles away to the north-west as the proverbial crow flies.

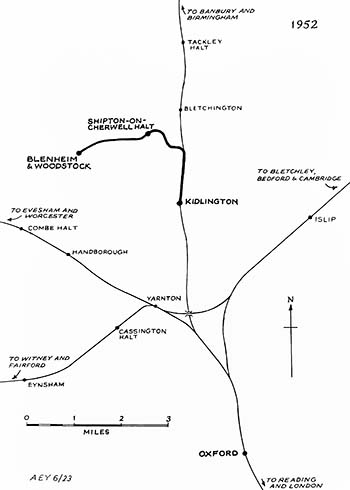

Planning for construction of the Woodstock branch had envisaged a physical junction at Shipton-on-Cherwell and at this point in the story it is worth providing an explanation to avoid any possible confusion. The village of Shipton-on-Cherwell was and is situated adjacent to and on the west side of the Oxford - Banbury line and should not be confused with the location of the later built Shipton-on-Cherwell Halt further west at Bunkers Hill. To keep matters simple the village will be referred in this page simply as ‘Shipton’ where reference to the village is necessary. It is convenient to mention here that some consideration had been given to providing a station or halt for Shipton but none was ever provided. But oddly, on the face of it, a terrace of railway cottages was built in the north-west corner of the village and on the south side of the Woodstock branch. They are still there, occupied, as of 2023. Were these cottages built due to a plan, later dropped, to provide a station or were they named ‘Railway Cottages’ merely because of their proximity to the branch line? At the time of writing this question remained unanswered.

1900 6" OS map.

1900 6" OS map.

It had been intended that the Woodstock branch be operated by the GWR from the outset which is indeed what happened, with the GWR taking over the financially troubled Woodstock Railway Company in 1897. It is therefore puzzling why the GWR suddenly decided a physical junction between the main line and the Woodstock branch at Shipton was not possible, merely stating that Woodstock branch trains could not operate over their metals to what was then still named Woodstock Road. Remember that the Woodstock company had no locomotives and rolling stock of its own, therefore the GWR was effectively banning operation of its own trains, operated by its own staff on its own metals. A possible reason may have been the need to provide the physical junction and a signal box at Shipton and partly, if not entirely at, at the expense of the GWR. The outcome was a separate bi-directional single line running along the Down side of the main line all the way from Shipton to what became Kidlington station. We will return to this matter later.

As we have already seen, the contractor for the Woodstock branch was Messrs. Lucas & Aird. Charles Lucas and Sir John Aird had their own separate businesses and it appears the Lucas & Aird partnership only swung into action for railway construction contracts. Their standard of workmanship was good but their understanding and control of finances was poor, if not reckless. Lucas & Aird had been involved with construction of the Hull & Barnsley Railway, full title ‘Hull, Barnsley & West Riding Junction Railway and Dock Company’ (which never actually reached Barnsley), under engineer William Shelford and had shown no financial acumen whatsoever. The excuse used by the contractor was the discovery of rock below the surface which had not been anticipated. While admittedly stumbling upon the unexpected was not exactly uncommon in those days, the rock excuse was to reappear at Woodstock when the authorised capital of £10,000 proved to be inadequate. Curiously Lucas & Aird were also the contractors for the Welsh Highland Railway and the same rock excuse also appeared there. Given the terrain the Welsh Highland Railway passed through, one would have thought encounters with rock would have been expected. Alarm bells should have rung at Blenheim Palace but John Aird was a personal friend and advisor to the Spencer-Churchills so it is possible the Duke was simply too trusting. At least one author has suggested the Duke had been unaware of the Hull & Barnsley fiasco but it is unlikely, on the face of it, a person of his standing would have been oblivious. The 8th Duke was, however, a financially inept figure and somewhat eccentric so quite to what extent Aird, in particular, influenced the Duke is open to speculation. Both Lucas and Aird ended up on the Board of the Woodstock railway by means of a quirk which saw them paid for their construction work in shares. This practice was not uncommon in the 19th century but it seems Charles Lucas and John Aird were unlikely to have ever been fully reimbursed. When the GWR bought out the Woodstock Railway Company in 1897 Charles Lucas had already died, in 1895 and in that year the Lucas & Aird partnership was dissolved. John Aird was John Aird junior - his father John Aird senior had died in 1876 - died in 1911.

Construction of what was to have been a 2 mile 40 chain single track railway between Blenheim & Woodstock and the junction at Shipton began in 1898 and a rather absurd comment, the source of which is unclear, was made to the effect that the line would be completed in just six weeks. The comment may have been based upon the appearance by 1898 of 'steam navvies' (mechanical excavators in modern parlance) and other mechanised equipment which heralded the end of much of the heavy work undertaken by means of hand tools. With the preliminaries, such as 'pegging out' the route, done, the heavy work commenced in April that year. Much of the line was built upon land owned by the Duke of Marlborough and some considerable engineering work was necessary, including a bridge over the Oxford Canal at Shipton. The problem here was the need to provide adequate clearance for canal boats. The GWR main line was on a low embankment and crossed the canal by means of canal bridge no. 219A while the junction for the Woodstock branch would have been some 200 yards further south near the River Cherwell bridge. The bridge carrying the Woodstock branch over the canal became canal bridge no. 219B (bridge 219 was and still is a lifting bridge over the canal located further east and therefore nothing to do with the railway). At this point the Woodstock branch was on a 14 chain radius curve and a 1:69 gradient rising in the Down direction. The line then entered a shallow cutting and passed beneath a bridge carrying the lane to Bunkers Hill; this lane later became an access road for the quarries on the north side of the railway. Further west there was a short ground level section before the railway again found itself on an embankment before crossing the Banbury Road on a bridge which originally sat in the middle of a four-way road junction; this junction was later altered to provide two 'T' junctions some 200 yards apart and was to become the location of Shipton-on-Cherwell Halt. From here the railway continued on an embankment with a gradient of 1:129 rising until in sight of Woodstock when it entered a fairly deep cutting itself crossed by two bridges, beyond which the line rose again to cross a skew bridge over Shipton Road, Hensington before regaining ground level to enter the terminus. In addition there were a number of cattle creeps and bridges for the benefit of farmers accessing their land. There were no public level crossings on the branch.

Meanwhile and with construction ongoing, the GWR had a change of mind and decided a station at Shipton was required but this never progressed beyond the discussion stage. What is fairly certain is that the GWR intended it to be a junction station which probably would have meant one side platform for the Up Main line and an island for the Down Main and branch or a Down Main platform with branch bay. Precisely where this never-to-be-built station would have been located is a matter of speculation. The reason this station was never built seems to have been down to cost, it being not allowed for in the authorised capital (which in any event had proved inadequate) and not mentioned in the original Act. The Woodstock Company had already purchased the required points and crossings for the intended junction at Shipton and this equipment was eventually purchased by the GWR.

Meanwhile and with construction ongoing, the GWR had a change of mind and decided a station at Shipton was required but this never progressed beyond the discussion stage. What is fairly certain is that the GWR intended it to be a junction station which probably would have meant one side platform for the Up Main line and an island for the Down Main and branch or a Down Main platform with branch bay. Precisely where this never-to-be-built station would have been located is a matter of speculation. The reason this station was never built seems to have been down to cost, it being not allowed for in the authorised capital (which in any event had proved inadequate) and not mentioned in the original Act. The Woodstock Company had already purchased the required points and crossings for the intended junction at Shipton and this equipment was eventually purchased by the GWR.

1900 6" OS map. Banbury Road Bridge is the site of Shipton on Cherwell Halt which opened in 1929,

1900 6" OS map. Banbury Road Bridge is the site of Shipton on Cherwell Halt which opened in 1929,

1938 25" OS map. The road junction has been realigned.

1938 25" OS map. The road junction has been realigned.

Despite the GWR not wanting branch trains on its main line, regardless of the fact they were to provide the trains and crews as already mentioned, plus the abandonment of the Shipton junction idea, the only remaining option was to lay a third track between Shipton and Woodstock Road (Kidlington). This is precisely what happened and the work was done surprisingly quickly. No additional Act was required for this the new line, although due to the GWR inserting some clauses, it was mentioned in an Act of 1890 which largely concerned the takeover of other railway companies by the GWR. No specific Act was required for the new line because it was to be built entirely on GWR land, but this itself raises a question. When the line north of Oxford was converted to standard gauge in 1869 it was done in the GWR's standard method of narrowing the gauge by means of moving the inside rails, leaving the 'six foot' (the distance between parallel tracks) wider than would be the case on lines built from the outset to the standard gauge and this legacy of the broad gauge can still be seen today. This was done north of Oxford so one has to wonder how space for an additional track was found and it can only be assumed the formation was widened within the bounds of GWR land. Even so it wasn't quite that simple as two bridges had to have an additional deck added and evidence of this remains visible today; widened bridge piers at Thrupp and an extant deck which, it must be made clear, is only assumed to have been a railway structure, accessed via a footpath from Shipton Bridge, near Holy Cross Church. The new line was ostensibly built by the GWR whereas in fact it was built by Messrs. Lucas & Aird on behalf of the GWR. The bi-directional single track had no junction with the main line until just north of Woodstock Road (Kidlington) station; therefore the new line extended the length of the Woodstock branch to 3 miles 57 chains. The ruling gradient on this new section south of Shipton was 1:522 and presumably still is in respect of the main line.

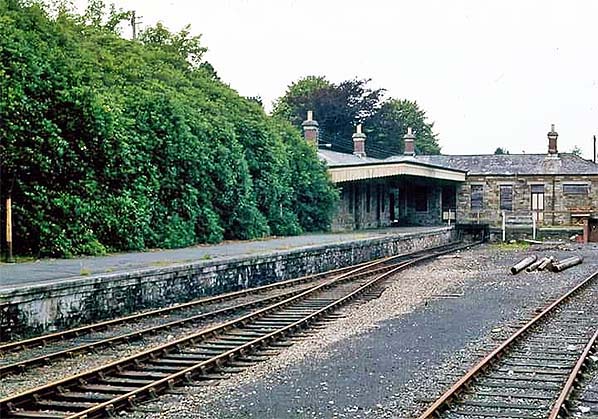

A very long way from Woodstock, this is Bodmin General station in 1977 and included to show the similarity to Blenheim & Woodstock station buildings. At this time the track into Bodmin General was still in use as here the Wenfordbridge clay traffic needed to reverse in order to reach Bodmin Road (now Bodmin Parkway) on the main line. At Bodmin the double doorway to the parcels office, right background, had been bricked up. The canopy is a different style from that at Woodstock and the chimneys have retained their pots - Woodstock station latterly lost them. Other than these unimportant points the buildings of the two stations were identical. The platform run-round loop was the same as at Woodstock prior to the rationalisation of the latter in 1926, but this feature was necessarily common to almost any branch terminus. Bodmin General is today part of a heritage railway and a second platform has been built to the right. Nevertheless while Bodmin General now sees plenty of passengers compared to Woodstock which saw few, a visit to it will give a flavour of what it would have been like to arrive at Woodstock by train.

A very long way from Woodstock, this is Bodmin General station in 1977 and included to show the similarity to Blenheim & Woodstock station buildings. At this time the track into Bodmin General was still in use as here the Wenfordbridge clay traffic needed to reverse in order to reach Bodmin Road (now Bodmin Parkway) on the main line. At Bodmin the double doorway to the parcels office, right background, had been bricked up. The canopy is a different style from that at Woodstock and the chimneys have retained their pots - Woodstock station latterly lost them. Other than these unimportant points the buildings of the two stations were identical. The platform run-round loop was the same as at Woodstock prior to the rationalisation of the latter in 1926, but this feature was necessarily common to almost any branch terminus. Bodmin General is today part of a heritage railway and a second platform has been built to the right. Nevertheless while Bodmin General now sees plenty of passengers compared to Woodstock which saw few, a visit to it will give a flavour of what it would have been like to arrive at Woodstock by train.

Photo by Alan Young

The new ‘third line of rails’, to use the official term of the time, was in theory the financial responsibility of the Woodstock Railway but this company was in no position to pay. Instead the GWR bore the cost and perhaps with some input from Lucas & Aird who were also investors in the Woodstock company. An agreement was reached whereby the Woodstock company would contribute £150 pa toward maintenance costs but this was to also fall upon the proverbial stony ground. Ultimately, in 1897, the GWR was to take over the Woodstock company.

The Woodstock branch was inspected for the Board of Trade by Colonel Frederick Henry Rich R.E., the rank of Colonel being honorary, with his actual rank upon retirement from the Army in February 1873 being Lieutenant-Colonel. He had in fact been seconded to the Board of Trade in 1861 but carried on the role after his retirement from the Army on 1 February 1873. An Irishman by birth, Colonel Rich died in Somerset on 22 August 1904 aged 80. The inspection of the Woodstock branch can be subject to some confusion as the Board of Trade advised the railway companies that Colonel Rich would carry out his inspection on 14 May 1890 which he duly did. For reasons which remain unclear, the Colonel produced one report for the section north to Shipton and another for the Shipton - Woodstock section which suggests two separate inspections. In fact the entire line was inspected that day and probably because until the branch was extended through to Woodstock Road there was no connection with the main line. The Colonel passed the line as fit to open with no recommendations and it duly opened on Monday 19 May 1890.

Until this time Woodstock Road station was a somewhat insignificant rural affair with short platforms capable of handling only local trains. The bay for Woodstock trains was provided behind the Down platform with the bufferstop at the north end of the station building. To provide the bay, the Down platform was considerably lengthened and to an extent way beyond what was actually necessary. The reason for this apparent extravagance is not known and after all longer through trains running onto the branch would have passed through Kidlington on the Down Main line. It is nevertheless possible the platform length was intended to cater for mixed trains comprising, say, locomotive, two passenger carriages and half a dozen or so goods wagons but if so the provision proved to be something of an overkill.

A few days later the Oxford Times portrayed the opening as a major local event which in some ways it was, but there was no ceremony, no flags and bunting, no band and indeed no other trappings of the kind usually, but not always, associated with railway openings. The very first train ran out from Oxford at 6.0AM with around 100 people onboard and appears to have been a special working, perhaps a positioning move to get rolling stock to the branch. The return journey from Woodstock carried some 200 people, many of whom were children from the adjacent National (Church of England) school, given time off for the occasion. This first day saw the branch carry a total of 432 passengers but thereafter and excepting the flurry of special trains during the 1890s the branch settled down to a relatively mundane existence. The Working Timetable for June 1890 showed one goods working at 7.0AM from Woodstock, returning from Kidlington (as Woodstock Road had by now been renamed) at 7.30AM with an arrival back at Woodstock at 7.40AM and five passenger trains per weekday of which none ran through to Oxford. Over the years the service increased to eight or nine passenger trains with some Oxford through workings, one goods (only) working which in later years ran only when required and one mixed working. There was an additional afternoon goods working which in later years was suspended.

1900 6" OS map>

1900 6" OS map>

Some traffic figures have survived and through the Edwardian period the number of tickets sold at Woodstock hovered around the 14,000 - 16,000 mark per year. The peak year was 1933 when the figure inexplicably rose to 23,295. In the same year the number of tickets sold at Kidlington was 6,680 but a good number of the latter may have been tickets sold for Oxford. After 1933 passenger figures gradually declined and while no figures appear to exist for the Second World War anecdotal evidence suggests the expected increase in business did not materialise, or at least not to any notable degree. Given there were other stations within a small radius, three to five miles, of Woodstock and on main lines perhaps this should not be surprising. Taking the peak figure of 23,295, while this might be respectable for a wayside station on a main line it was quite dire for the Woodstock branch which relied largely upon revenue collected at the terminus. Allowing for there being no Sunday service it equates approximately to 78 passengers per day which equates to 8.6 passengers per train assuming a nine trains per day service. Many of those passengers would have travelled in the morning and evening peaks, if it can be said the Woodstock branch had peaks, and on the Oxford through trains. Even when allowing for tickets sold at Kidlington it is easy to see why several trains ran empty or at best with just one or two passengers. Figures for Shipton-on-Cherwell Halt are not available. There were a number of season ticket holders, however. In 1923 for example there were 236 - a surprisingly high figure, but by 1933 the figure had fallen to a mere 22.

Some traffic figures have survived and through the Edwardian period the number of tickets sold at Woodstock hovered around the 14,000 - 16,000 mark per year. The peak year was 1933 when the figure inexplicably rose to 23,295. In the same year the number of tickets sold at Kidlington was 6,680 but a good number of the latter may have been tickets sold for Oxford. After 1933 passenger figures gradually declined and while no figures appear to exist for the Second World War anecdotal evidence suggests the expected increase in business did not materialise, or at least not to any notable degree. Given there were other stations within a small radius, three to five miles, of Woodstock and on main lines perhaps this should not be surprising. Taking the peak figure of 23,295, while this might be respectable for a wayside station on a main line it was quite dire for the Woodstock branch which relied largely upon revenue collected at the terminus. Allowing for there being no Sunday service it equates approximately to 78 passengers per day which equates to 8.6 passengers per train assuming a nine trains per day service. Many of those passengers would have travelled in the morning and evening peaks, if it can be said the Woodstock branch had peaks, and on the Oxford through trains. Even when allowing for tickets sold at Kidlington it is easy to see why several trains ran empty or at best with just one or two passengers. Figures for Shipton-on-Cherwell Halt are not available. There were a number of season ticket holders, however. In 1923 for example there were 236 - a surprisingly high figure, but by 1933 the figure had fallen to a mere 22.

Photographed crossing the Oxford Canal bridge, Shipton on Cherwell, the Woodstock-bound autotrain is headed by 0-6-0PT No. 5413 in British Railways days. The train has just parted company with the main line, which is visible in the background through the bridge. Moments later the train would enter a cutting and pass beneath the bridge carrying a lane from Shipton to Bunkers Hill over the line. The train will arrive at Woodstock just four minutes later, having in the meantime called at Shipton on Cherwell Halt. The autotrailer appears to be devoid of passengers, or possibly there is just a single passenger. Unfortunately this was all-but the norm for the Woodstock branch by this time and indeed for many other rural branch lines. The photograph was taken from the canal towpath and the location can be accessed today by the same means and although the bridge deck has long gone the brick section complete with arch is still there as of 2023 but now quite overgrown. The gate beneath the arch was probably to prevent cattle straying.

Photographed crossing the Oxford Canal bridge, Shipton on Cherwell, the Woodstock-bound autotrain is headed by 0-6-0PT No. 5413 in British Railways days. The train has just parted company with the main line, which is visible in the background through the bridge. Moments later the train would enter a cutting and pass beneath the bridge carrying a lane from Shipton to Bunkers Hill over the line. The train will arrive at Woodstock just four minutes later, having in the meantime called at Shipton on Cherwell Halt. The autotrailer appears to be devoid of passengers, or possibly there is just a single passenger. Unfortunately this was all-but the norm for the Woodstock branch by this time and indeed for many other rural branch lines. The photograph was taken from the canal towpath and the location can be accessed today by the same means and although the bridge deck has long gone the brick section complete with arch is still there as of 2023 but now quite overgrown. The gate beneath the arch was probably to prevent cattle straying.

Photo from John Mann collection

We must not ignore goods traffic on the Woodstock branch and discounting, to keep things simple, parcels and sundries carried by passenger train, some figures are 8,504 tons in 1923 and peaking at 12,047 tons in 1926. Thereafter came a steady decline, falling to 7,303 tons in 1933. Unfortunately and as with passenger traffic, goods figures for the Second World War are not available. The railway was never to recover and as already mentioned the daily goods working was later suspended with what goods traffic remained, when there was any, being taken by mixed train. Goods traffic on the Woodstock branch never had much variety, being largely coal, minerals and occasional deliveries of leather for the town's glove factories. Indeed goods traffic was usually so light that shunting was frequently done by the branch locomotive with the autotrailer still attached. The same applied at Kidlington when any wagons were to be dropped off or collected.

Shipton-on-Cherwell Halt opened in 1929 primarily to serve the cement works’ cottages on Bunkers Hill. It is worth mentioning that although the cement works are quarries where rail connected this was not via the Woodstock branch. Instead, exchange sidings were located on the Down side of the main line between Shipton and Bletchington and known as ‘Bletchington Sidings’. The cement works was opened in 1929, the same year as Shipton-on-Cherwell Halt, by the Oxford & Shipton Cement Co. Ltd. Cement production ceased in 1987 under APCM ownership. Part of the quarry remained in operation into the 2020s but much of the site had become a Site of Special Scientific Interest with proposals for house building on the former cement works site.

Sometime in British Railways days 0-4-2T No. 1442 was caught at Shipton on Cherwell with a service from Woodstock. The fireman is watching the photographer while the youngster on the platform appears to be intent on watching the train depart. No. 1442 was shedded at Oxford between February and March 1951 and again from December 1953 until November 1962 so the photograph could date from either period, the latter up until closure of the Woodstock branch in 1954 of course. No. 1442 along with No. 1450 were destined to be the final members of the 14xx class in service, being withdrawn on 7 May 1965. No. 1442 ended her BR days on the Tiverton Junction - Tiverton shuttle. She survived into preservation, minus auto equipment, to be plinthed for many years exposed to the elements. She was subsequently cosmetically restored and now resides inside Tiverton museum but whether she will ever be extricated and steamed again remains to be seen.

Sometime in British Railways days 0-4-2T No. 1442 was caught at Shipton on Cherwell with a service from Woodstock. The fireman is watching the photographer while the youngster on the platform appears to be intent on watching the train depart. No. 1442 was shedded at Oxford between February and March 1951 and again from December 1953 until November 1962 so the photograph could date from either period, the latter up until closure of the Woodstock branch in 1954 of course. No. 1442 along with No. 1450 were destined to be the final members of the 14xx class in service, being withdrawn on 7 May 1965. No. 1442 ended her BR days on the Tiverton Junction - Tiverton shuttle. She survived into preservation, minus auto equipment, to be plinthed for many years exposed to the elements. She was subsequently cosmetically restored and now resides inside Tiverton museum but whether she will ever be extricated and steamed again remains to be seen.

Photo from Jim Lake collection

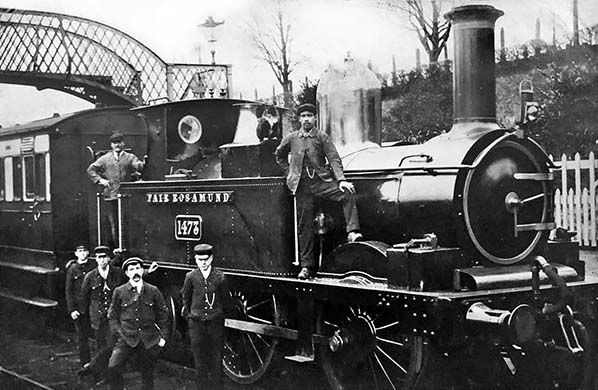

One thing the Woodstock branch lacked throughout its life was motive power variety and from opening until closure 0-4-2T tanks predominated while until 1926 a locomotive was shedded, or perhaps more accurately outstationed, at Woodstock. For many years this was a 517 Class including the long-time resident ‘Fair Rosamund’. Following this 48xx/14xx Class locomotives took over, with No. 1420 being on duty on the final day. Not infrequently one or other type of 0-6-0PT would appear, deputising for an 0-4-2T but Oxford sometimes sent out a Pannier Tank which was not auto fitted which meant running round was necessary at each end of the line. At Kidlington this meant first unloading any passengers before reversing out of the station to perform the run-round. After 1926 the same was necessary at Woodstock and turn round time at both Woodstock and Kidlington was sometimes tight - ten or twelve minutes. Despite their long time on the branch the 0-4-2Ts were not entirely suited due to wet or frosty rails on the curve at Shipton and with mixed trains. Crews much preferred the 0-6-0PTs providing they got one which was auto fitted. The GWR denoted Route Availability by means of colour codes with what would be RA1 on other railways being uncoloured. The Woodstock branch was coded yellow, which meant the maximum permitted axle load was 16 tons. Axle Load of the 517 Class was 12t 16cwt and of the 4800/1400 Class 13t 18cwt. Both these classes were uncoloured while the 5400 Class Pannier Tanks were coded yellow, having an axle load of 15t 12cwt.

No. 1473 'Fair Rosamund' has come to be synonymous with the Woodstock branch but she was no means confined to the branch and from time to time would 'escape' to visit other lines. She is seen here at what is thought to be Chipping Norton, on the long-since-abandoned King's Sutton - Kingham line. Photographs of No. 1473 are not rare but good quality close-up views are hard to come by, hence the inclusion of this photograph. She is seen here with her original style boiler with round-topped firebox. In 1915 she was given a new boiler with Belpaire firebox and therefore this photograph predates 1915. In due course she would also receive a full cab while number plates would be positioned nearer the cab to make room for the 'GREAT WESTERN' title on the tank sides. The result was not very aesthetically pleasing. The occasion at Chipping Norton was probably nothing more than one of the group staff photographs which were very common at the time. However, the proceedings were being supervised by the apparently well-fed station cat from its vantage point on the locomotive's toolbox. Clearly the cat was well used to the sounds of steam locomotives; after all no cat could act as station supervisor otherwise.

No. 1473 'Fair Rosamund' has come to be synonymous with the Woodstock branch but she was no means confined to the branch and from time to time would 'escape' to visit other lines. She is seen here at what is thought to be Chipping Norton, on the long-since-abandoned King's Sutton - Kingham line. Photographs of No. 1473 are not rare but good quality close-up views are hard to come by, hence the inclusion of this photograph. She is seen here with her original style boiler with round-topped firebox. In 1915 she was given a new boiler with Belpaire firebox and therefore this photograph predates 1915. In due course she would also receive a full cab while number plates would be positioned nearer the cab to make room for the 'GREAT WESTERN' title on the tank sides. The result was not very aesthetically pleasing. The occasion at Chipping Norton was probably nothing more than one of the group staff photographs which were very common at the time. However, the proceedings were being supervised by the apparently well-fed station cat from its vantage point on the locomotive's toolbox. Clearly the cat was well used to the sounds of steam locomotives; after all no cat could act as station supervisor otherwise.

Photo from Jim Lake collection

The two 517 Class locomotives most often seen on the Woodstock branch, in terms of being photographed, were No. 1473 ‘Fair Rosamund’, of course, and No. 1159. During an undefined period in the early years of the 20th century both Nos. 1159 and 1473 spent time on the Abingdon branch, being outstationed at that station's engine shed, although of course not both at the same time. It appears these locomotives were swapped around between the Abingdon and Woodstock branches, perhaps as a result of juggling around due to overhauls and repairs. Questions remain concerning the nameplates of No. 1473. It has been suggested they comprised cast brass letters mounted onto wooden baseplates and if true the implication is the plates were manufactured 'on the cheap' and perhaps not intended to be permanent. Mention has been made elsewhere regarding the ‘Fair Rosamund’ nameplates not known to have survived. At around the 1970s - 1980s period rumours circulated that one nameplate had survived and was, then, somewhere in the Woodstock area but no evidence of this has been found and the story appears to have been a myth.

In 1908 a steam railmotor appeared on the Woodstock branch as part of the GWR's 'Oxford Suburban Service' which in reality was a hotch-potch of odd services over various lines or sections thereof (see the photograph of a railmotor at Woodstock). The railmotor is known to have initially worked one round trip between Oxford and Woodstock and later a second late afternoon round trip but for how long is unclear. There was also a late evening Saturdays Only railmotor service. The railmotor called in addition at Wolvercot Halt, soon renamed to Wolvercot Platform to avoid confusion with Wolvercote Halt on the L&NWR line out of Oxford. Note the different spellings, Wolvercot and Wolvercote. Wolvercot was a railmotor halt situated between Oxford and Kidlington and despite its lowly status was originally staffed and had a stationmistress, a Miss Margaret Elsden. Her brother was at one point in time stationmaster at Birmingham Snow Hill and she later married a Frank Buckingham who was, or became, stationmaster at Oxford General. Wolvercot Halt/Platform was short lived, existing only between 1908 and 1916. It perhaps should be mentioned that ‘Railmotor’ is something of a colloquial term which over time has become the accepted term. The Great Western Railway usually used the term ‘Rail Motor Car

Steam railmotor No. 74 is here caught by the camera on the afternoon Woodstock - Oxford working on Friday 12 June 1914. The railmotor has just departed Wolvercot Platform as a crew member looks back along the car, which appears to still wear the practical but rather unattractive unlined brown livery replaced from 1912 by the more attractive lined Crimson Lake livery. The service was part of what the GWR called its 'Oxford Suburban Service' but this involved only two trips on the Woodstock branch, this one which ran Monday to Saturday and a Saturdays Only late evening 11.05PM Oxford - Woodstock and 11.33PM return. The afternoon working departed Oxford at 1.55PM and returned from Woodstock at 2.52PM. These railmotor workings, the timings of which probably varied slightly over the years, appear to have been in addition to the normal branch trains. The railmotor is towing a 'Cordon' gas tank wagon and this is described further in the Woodstock station text. As seen here the wagon will be an empty returning to Oxford and in all likelihood the railmotor had dropped off a charged wagon at Woodstock. No. 74 had been new to traffic in April 1906 and was withdrawn in June 1933 for conversion to an autotrailer. In this latter form she reappeared in February 1934 as No. 203 and lived on, as most did, to see service with British Railways. As BR No. W203W she was officially withdrawn in March 1958 but for reasons unconfirmed remained in service until December of that year. A possible reason was the general poor condition of these vehicles by the 1950s, with W203W being found in better condition than another for which withdrawal was the only option. If so this many have been car W135W which is the only other autotrailer shown as being withdrawn in March 1958.

Steam railmotor No. 74 is here caught by the camera on the afternoon Woodstock - Oxford working on Friday 12 June 1914. The railmotor has just departed Wolvercot Platform as a crew member looks back along the car, which appears to still wear the practical but rather unattractive unlined brown livery replaced from 1912 by the more attractive lined Crimson Lake livery. The service was part of what the GWR called its 'Oxford Suburban Service' but this involved only two trips on the Woodstock branch, this one which ran Monday to Saturday and a Saturdays Only late evening 11.05PM Oxford - Woodstock and 11.33PM return. The afternoon working departed Oxford at 1.55PM and returned from Woodstock at 2.52PM. These railmotor workings, the timings of which probably varied slightly over the years, appear to have been in addition to the normal branch trains. The railmotor is towing a 'Cordon' gas tank wagon and this is described further in the Woodstock station text. As seen here the wagon will be an empty returning to Oxford and in all likelihood the railmotor had dropped off a charged wagon at Woodstock. No. 74 had been new to traffic in April 1906 and was withdrawn in June 1933 for conversion to an autotrailer. In this latter form she reappeared in February 1934 as No. 203 and lived on, as most did, to see service with British Railways. As BR No. W203W she was officially withdrawn in March 1958 but for reasons unconfirmed remained in service until December of that year. A possible reason was the general poor condition of these vehicles by the 1950s, with W203W being found in better condition than another for which withdrawal was the only option. If so this many have been car W135W which is the only other autotrailer shown as being withdrawn in March 1958.

Photo by Ken Nunn

The GWR built up a large fleet of steam railmotors, ninety-nine plus one petrol railcar and persisted with them more than other companies were prepared to do although interestingly one former L&NWR steam railmotor managed to survive, just, to work for British Railways on Scotland's Moffat branch. Nevertheless the inherent problems with steam railmotors eventually dawned upon the GWR and through the 1920s and 1930s the majority were converted into autotrailers. Thus the autotrailer was looming on the horizon for the Woodstock branch. ‘Autotrailer’, either in one or two word form, is a rather colloquial term which has become entrenched but the GWR and to an extent British Railways Western Region used the term ‘Auto-car’. Some autotrailers were built as steam railmotor trailers, such as the preserved No. 92 and needed little if any modification but the majority were either conversions from railmotors or built new. The latter category continued to be built under British Railways until 1953 although the very last batch, car nos. 245 - 256, were rebuilds from older Brake Thirds. As far as is known, none of autotrailers built new as such ever operated on the Woodstock branch. On the GWR, control from the driving cab was via mechanical linkage to the locomotive but operation of the reverser was the job of the fireman who of course remained on the locomotive at all times. Other railway companies used the terms ‘Pull & Push’ or ‘Push & Pull’ and the control system from the remote cab could be air or vacuum operated depending upon braking systems used by different companies.

With the Woodstock branch closing in 1954 diesel traction was rare and there is just one confirmed appearance along with the possibility of the track lifting contractor using a small diesel, or petrol, shunting locomotive. In July 1949 an ex GWR diesel railcar appeared on the Woodstock branch. The branch autotrain ran through to Oxford as the 12.58PM from Woodstock and then escaped to cover a round trip on the Oxford - Princes Risborough line. The diesel railcar then took over, working 2.30PM to Woodstock, 3.50PM to Kidlington, 4.10PM to Woodstock, 5.22PM to Kidlington. At Kidlington the railcar lingered until 5.55PM when it ran in service, but unadvertised, to Oxford and thereafter worked the Princes Risborough line with the autotrain, having arrived back at Oxford, then returning to the Woodstock branch. The use of the diesel railcar appears to have been the result of diagramming rather than an attempt to modernise the Woodstock branch and in any case its use on Woodstock services was short lived. Unfortunately no photographs of the diesel railcar on the Woodstock branch have come to light.

This view is difficult to date and not helped by none of the posters being identifiable; does anybody recognise any of them? Judging by the clothing of the, presumably, mother and her children entering the ticket office we could be looking at circa 1950. On the right is the familiar GWR 'spearhead' fencing, some of which survived in 2023 around the corner in New Road. Given this is Oxfordshire one might expect loyalty to dictate the motor car is a [prewar] Morris Minor. It is in fact an Austin Seven with AA badge mounted prominently on its grille.

This view is difficult to date and not helped by none of the posters being identifiable; does anybody recognise any of them? Judging by the clothing of the, presumably, mother and her children entering the ticket office we could be looking at circa 1950. On the right is the familiar GWR 'spearhead' fencing, some of which survived in 2023 around the corner in New Road. Given this is Oxfordshire one might expect loyalty to dictate the motor car is a [prewar] Morris Minor. It is in fact an Austin Seven with AA badge mounted prominently on its grille.

Photo from John Mann collection

A glance at Oxford shed's allocations at the time shows several diesel railcars on its books but all were of the earlier streamlined type nicknamed ‘Flying Bananas’. These earlier cars comprised Nos. 1 - 17 with No. 17 being a dedicated parcels car. No. 18 was an odd man out being fitted as a prototype for the later batch of 'razor edge' cars with proper buffing and drawgear. No. 18 was a long time resident on the Lambourn branch. Thus cars 1 -17 could not tow a trailing load whereas car 18 and onwards could and did but in the form or an ordinary passenger carriage or fitted (brake fitted) van. The use therefore of one of the earlier cars on the Woodstock branch was limited to passenger-only services and even if one of the later cars with buffing and drawgear had been used these cars were not really suitable for mixed train working or shunting of wagons at Woodstock. This means that while it may appear to have been common sense to convert the Woodstock branch entirely to diesel railcar operation, thereby reducing operating costs, a steam locomotive would still have been required for goods workings and shunting making economy of operation less attractive than may be imagined.

With the visitation of the diesel railcar passing into history the Woodstock branch plodded on much the same as before with its autotrain and mixed working. The goods-only working which was latterly 'As Required' rarely ran and the mixed train, using Woodstock allocated 'Toad' brake van W68776, usually sufficed.

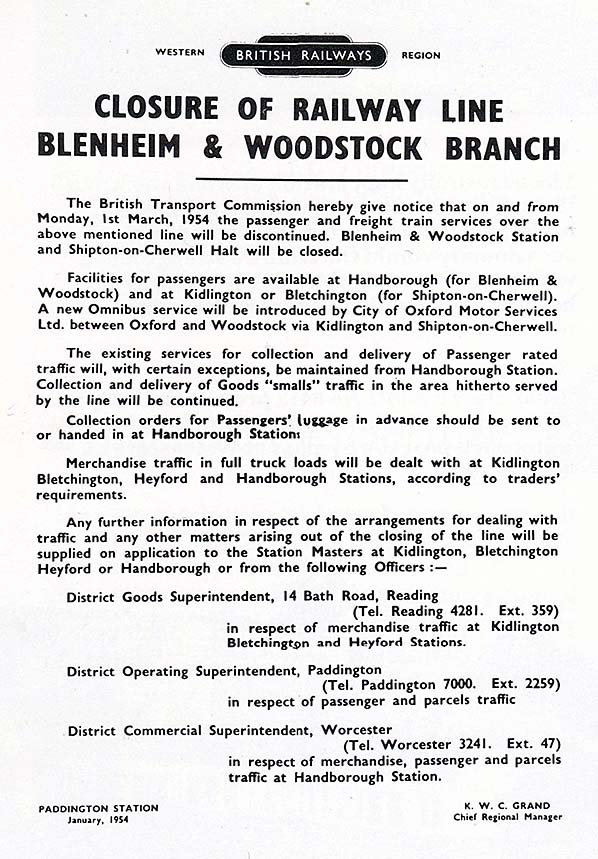

Closure of the Woodstock branch in 1954 is well covered by photographs and their captions so the events of the final day need not be repeated here. Nevertheless it is worth taking a look at the factors which led to the demise of the branch which occurred some years before most people had even heard of Dr. Beeching. These factors can be summarised as inconvenient passenger services, the location of Woodstock relative to Oxford and other railways, the growth of road motor transport. Regarding passenger services, the Oxford through trains were popular but even so a single autotrailer was adequate for passenger numbers. Other trains shuttled to and from Kidlington which at the time had little to attract people from outside and main line connections often involved a wait of half an hour or more. Regarding the location of Woodstock, as we have already seen there were other stations on main lines in the area which were more suited to people travelling north or west. It must be remembered that in the days before road motor transport rural people, who at one time rarely travelled far from their home area, thought nothing of walking three, four or more miles or using some form of horse drawn vehicle. In this respect the Woodstock branch came too late to effect any significant change and in part because the network of local carriers was well established. Regarding the growth of road motor transport, this effected railways everywhere and in particular rural railways. Road motor transport began to attack the railways after the First World War when demobbed service personnel bought military surplus vehicles and set up haulage and/or passenger transport businesses. The vehicles and roads of the time were really suitable only for local and medium distance journeys but for rural branch lines this was enough to start a decline. Railway companies including the GWR did operate their own road services, goods and passenger, which were for many years quite successful but they were never really designed to compete with private road transport operators. The opening of lineside halts was an attempt to capture passenger business from road transport operators, Wolvercot Platform being an example, but these halts were only moderately successful.

The subject of road passenger transport serving Woodstock and the town's proximity to Oxford warrants a closer examination. The City of Oxford & District Tramway Company ran a horse tram system and in 1906 was taken over by the City of Oxford Electric Tramway Company. In an almost mirror image of Cambridge, tramway electrification was opposed and the last horse trams clip-clopped through the streets in 1914. The Oxford company decided to operate the new-fangled motor omnibuses instead and in 1921 was renamed City of Oxford Motor Services Limited (COMS) which became well known for its smart fleet of mostly AEC vehicles in 'maroon and duck egg green' livery. COMS quickly expanded its routes well beyond the boundary of the City of Oxford and this included to Woodstock. The service was frequent, relative to the trains, and of course all services took people to and from the centre of Oxford. No wonder British Railways threw in the proverbial towel in 1954. Nevertheless and as would be required under the terms of closure, the COMS provided a rail replacement omnibus linking Woodstock, Bunkers Hill, Shipton-on-Cherwell and Kidlington with Oxford. As was the case with most such services it does not seem to have lasted long. A glance at COMS timetables from the 1960s shows a half-hourly omnibus service to and from Oxford reducing to approximately hourly in the evenings. This level of service suggests that by the 1960s the demand was there but the railway, with its mere eight trains per day most of which required a change at Kidlington, would not have been able to compete had it survived just a few more years to see the introduction of diesel multiple-units

The subject of road passenger transport serving Woodstock and the town's proximity to Oxford warrants a closer examination. The City of Oxford & District Tramway Company ran a horse tram system and in 1906 was taken over by the City of Oxford Electric Tramway Company. In an almost mirror image of Cambridge, tramway electrification was opposed and the last horse trams clip-clopped through the streets in 1914. The Oxford company decided to operate the new-fangled motor omnibuses instead and in 1921 was renamed City of Oxford Motor Services Limited (COMS) which became well known for its smart fleet of mostly AEC vehicles in 'maroon and duck egg green' livery. COMS quickly expanded its routes well beyond the boundary of the City of Oxford and this included to Woodstock. The service was frequent, relative to the trains, and of course all services took people to and from the centre of Oxford. No wonder British Railways threw in the proverbial towel in 1954. Nevertheless and as would be required under the terms of closure, the COMS provided a rail replacement omnibus linking Woodstock, Bunkers Hill, Shipton-on-Cherwell and Kidlington with Oxford. As was the case with most such services it does not seem to have lasted long. A glance at COMS timetables from the 1960s shows a half-hourly omnibus service to and from Oxford reducing to approximately hourly in the evenings. This level of service suggests that by the 1960s the demand was there but the railway, with its mere eight trains per day most of which required a change at Kidlington, would not have been able to compete had it survived just a few more years to see the introduction of diesel multiple-units

Not long before closure the branch autotrain headed by 5400 Class 0-6-0PT No. 5413 slows through the cutting on its approach to Woodstock. The train has just passed Woodstock fixed distant signal. Such signals were not controlled and were permanently set at 'caution' to remind drivers the end of the line was ahead. The signal arm is barely visible - it is pointing to the right as we look at it. The photograph was taken from the bridge carrying Sansom's Lane over the line. Sansom's Lane is just a dirt track public footpath. The bridge visible in the distance was provided for the local farmer to access fields on both sides of the line. Note the wooden gangers’ hut behind and to the left of the signal. Having passed beneath the bridge upon which stands the photographer the autotrain will find itself on embankment and will cross the bridge over Shipton Road, Hensington before arriving at Woodstock terminus within a couple of minutes of being photographed. Today this cutting is infilled and it is thought the farmer's bridge, at least, is still in existence but buried.

Not long before closure the branch autotrain headed by 5400 Class 0-6-0PT No. 5413 slows through the cutting on its approach to Woodstock. The train has just passed Woodstock fixed distant signal. Such signals were not controlled and were permanently set at 'caution' to remind drivers the end of the line was ahead. The signal arm is barely visible - it is pointing to the right as we look at it. The photograph was taken from the bridge carrying Sansom's Lane over the line. Sansom's Lane is just a dirt track public footpath. The bridge visible in the distance was provided for the local farmer to access fields on both sides of the line. Note the wooden gangers’ hut behind and to the left of the signal. Having passed beneath the bridge upon which stands the photographer the autotrain will find itself on embankment and will cross the bridge over Shipton Road, Hensington before arriving at Woodstock terminus within a couple of minutes of being photographed. Today this cutting is infilled and it is thought the farmer's bridge, at least, is still in existence but buried.

Photo from Jim Lake collection

Across the country there were numerous branch lines which soldiered on after the withdrawal of passenger services. Their staple was coal traffic and, often, seasonal agricultural traffic. In the case of Woodstock coal could be easily handled at other nearby mainline stations and transported from there by road or from the centralised Coal Concentration Depots set up by British Rail. The local coal merchant with an office in Woodstock goods yard was James Marriott. This firm was based at Witney but had coal depots at several stations in the region, some of which are still open today, so would not have been especially inconvenienced by the closure of the railway to Woodstock. As we have seen, Shipton-on-Cherwell cement works and quarries were served by the main line and the Woodstock Branch played no part in this traffic. It was arranged for remaining goods traffic, namely coal and leather, to be dealt with at Hanborough, to use the present spelling, station where, as it happened, Marriott also had premises.

So it was that at 7.10PM on Saturday 27 February 1954 0-4-2T No. 1420 with autotrailer No. W183W operated the final train from Blenheim & Woodstock. Driver Harry Collins was at the controls. Normally the running time to Kidlington was ten minutes but for some reason the 7.10PM was allowed fifteen minutes and the reason can be found by a check of timetables. The 7.10PM ran as empty stock from Kidlington to Oxford and for that reason arrived at Kidlington's Up Main platform rather than the Down side bay. To do this it had to cross from the branch, which was on the Down side, to the Up Main line. The extra five minutes can be explained by the ex-Woodstock train being held at a signal to await the passing of the 6.10PM Paddington - Wolverhampton express. Having arrived at Kidlington's Up Main platform the empty stock departure was at 7.25PM but on the final day it continued to Oxford in service due to a number of enthusiasts onboard wishing to reach Oxford. This sort of helpful co-operation on the part of British Railways was not uncommon. The official closure date of the Woodstock branch was Monday 1 March 1954 and it was presumably on the Monday the remaining wagons and autotrailer which had been left at Woodstock were removed from the branch. The reason why this second autotrailer was detached from the train during the afternoon and not returned to Oxford that day has not been discovered although one possibility is that it had developed a defect.

British Railways were in no great hurry to dismantle the branch and Messrs. Pittrail Limited commenced this work sometime in late 1957 and completed the work early in January 1958. Very few details of the track lifting operation are known. Not all the branch was lifted, however. A section of some 40 chains (about half a mile) northwards from Kidlington was left in situ for use as a refuge siding and is thought to have finally been removed in 1968 (see below). In the years subsequent to the dismantling of most of the Woodstock branch various changes took place. The cutting along the northern edge of Shipton village was infilled and from there for a short distance westward a quarry road was laid on the formation. The embankment either side of Banbury Road, the location of Shipton-on-Cherwell Halt, survives but is now heavily wooded. The cutting between Banbury Road and Woodstock was also infilled and beyond this, on the approach to Woodstock, part of the formation is now The Old Woodstock Line Nature Reserve and the remainder of the line to the extant terminus buildings is now built on. With a couple of possibly buried exceptions, the sites of which are on private land, all bridges were removed, leaving just abutments standing. In Woodstock the site of the skew bridge over Shipton road offers no clue that a railway once existed. To perhaps gladden the hearts of railway enthusiasts, all examples of the 14xx Class 0-4-2T locomotives which have survived into preservation are known to have worked the Woodstock branch at various times, while a number of autotrailers of various types have also survived.

British Railways were in no great hurry to dismantle the branch and Messrs. Pittrail Limited commenced this work sometime in late 1957 and completed the work early in January 1958. Very few details of the track lifting operation are known. Not all the branch was lifted, however. A section of some 40 chains (about half a mile) northwards from Kidlington was left in situ for use as a refuge siding and is thought to have finally been removed in 1968 (see below). In the years subsequent to the dismantling of most of the Woodstock branch various changes took place. The cutting along the northern edge of Shipton village was infilled and from there for a short distance westward a quarry road was laid on the formation. The embankment either side of Banbury Road, the location of Shipton-on-Cherwell Halt, survives but is now heavily wooded. The cutting between Banbury Road and Woodstock was also infilled and beyond this, on the approach to Woodstock, part of the formation is now The Old Woodstock Line Nature Reserve and the remainder of the line to the extant terminus buildings is now built on. With a couple of possibly buried exceptions, the sites of which are on private land, all bridges were removed, leaving just abutments standing. In Woodstock the site of the skew bridge over Shipton road offers no clue that a railway once existed. To perhaps gladden the hearts of railway enthusiasts, all examples of the 14xx Class 0-4-2T locomotives which have survived into preservation are known to have worked the Woodstock branch at various times, while a number of autotrailers of various types have also survived.

Brick and girder bridge carrying a privte road oiver the cutting near Shipton-on-Cherwell in March 1957. The bridge is still standing alsthough the cutting has has been almopst entirely filled with rubbish.

Brick and girder bridge carrying a privte road oiver the cutting near Shipton-on-Cherwell in March 1957. The bridge is still standing alsthough the cutting has has been almopst entirely filled with rubbish.

Photo by RM Casserley

Kidlington station, meanwhile, had closed on 2 November 1964. Subsequent to 1926 Kidlington signal box became the only 'box with control over the Woodstock branch and because of this it is worth giving some details. The original Woodstock Road 'box is believed the have closed in May 1890 to be replaced at the same time by Kidlington 'box. This seems to have been a new or perhaps rebuilt 'box with the name coinciding with the change of name of the station. No details of Woodstock Road 'box are known. Kidlington 'box was a Great Western Railway Type 5 structure and was fitted with a Great Western Railway Type HT3 51-lever frame. It would have been commissioned shortly before the Woodstock branch opened to traffic. The 'box closed on 16 September 1968 which was likely to have been the same day as the refuge siding, the by-then-surviving stub of the Woodstock branch (ref. above), was taken out of use, thereby marking the final demise of the Woodstock branch. Kidlington 'box was demolished in 1970.

Kidlington station, meanwhile, had closed on 2 November 1964. Subsequent to 1926 Kidlington signal box became the only 'box with control over the Woodstock branch and because of this it is worth giving some details. The original Woodstock Road 'box is believed the have closed in May 1890 to be replaced at the same time by Kidlington 'box. This seems to have been a new or perhaps rebuilt 'box with the name coinciding with the change of name of the station. No details of Woodstock Road 'box are known. Kidlington 'box was a Great Western Railway Type 5 structure and was fitted with a Great Western Railway Type HT3 51-lever frame. It would have been commissioned shortly before the Woodstock branch opened to traffic. The 'box closed on 16 September 1968 which was likely to have been the same day as the refuge siding, the by-then-surviving stub of the Woodstock branch (ref. above), was taken out of use, thereby marking the final demise of the Woodstock branch. Kidlington 'box was demolished in 1970.

Young's Garage occupied the Woodstock station building in October 1979.

Young's Garage occupied the Woodstock station building in October 1979.

Photo by Alan Young

There is an aerial view based on Google Earth showing the remains of the Woodstock branch in 2021 at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wxOQmE6uYv8

Sources and bibliography:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

The Steam Rail Motors of the Great Western Railway, Gibbs, The History Press 2015 ISBN 978 0 7509 6103 5

-

Great Western Infrastructure 1922 - 1934: Photographs from the E. Wallis Collection:

-

See Blenheim and Woodstock, Shipton-on-Cherwell Halt and Kidlington