Records of the Great Eastern Railway from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries show a not inconsiderable number of bridge repairs and, in some cases, reconstructions. Some, but by no means all, of the reconstructions were for purposes of widening, but whatever the reasons for these works may have been, it would have required a financial outlay as well as causing inconvenience to traffic so the rebuilding of the Abington Road bridge could have been an experiment to reduce the frequency of bridge works. This would, in fact, seem to be the only logical explanation. We can discount any reconstruction of the Newmarket - Chesterford section as being the reason; reopening petitions appeared from time to time but had fizzled out by the 1890s and, in any event, all were rejected without getting beyond the boardroom.

Thanks to the efforts of the Great Eastern Railway Society a number of GER documents have been saved from destruction. Among these is a GER drawing of a number of bridges and two level-crossings in Cambridge and Cambridgeshire. The drawing is undated but surviving GER minutes indicate that it dates from 1915. The drawing is connected with Cambridgeshire County Council road repairs and unlike all other bridges on the drawing that at 'Babraham, over disused Newmarket line' does not have a bridge number. This suggests that by 1915 the railways were no longer responsible for the bridge*, so the rebuilding work was likely to have been the result of a highways scheme involving Atlas, or whoever was indeed responsible for the construction side. Subsequent to the initial research for this article, it has come to light that a further GER drawing, including this bridge, has survived from 1910. Again, this concerns road repairs and has nothing to do with the rebuilding of the bridge. In any case, these drawings are almost certainly too early for any possible connection with Atlas Concrete's Cambridge works. The drawings, it is worth adding, are in Plan view only so are of little, if any, help in determining the design of the bridge - even if dates were to all tie in conveniently.

*It is known from surviving Eastern Counties Railway (ECR) records that when the Chesterford section was abandoned, payments-in-settlement were made in respect of ‘turnpikes’: in other words, the ECR was ridding itself of any continued liability for road maintenance at level crossings on turnpike roads. In view of this it is likely the ECR attempted to rid itself of all responsibilities on the line of route subsequent to the Abandonment Act of 1858. Certainly, after the 1858 Act, little time was wasted selling off the redundant trackbed and this was one of the reasons stated by the GER for rejection of one of the reopening petitions mentioned earlier.

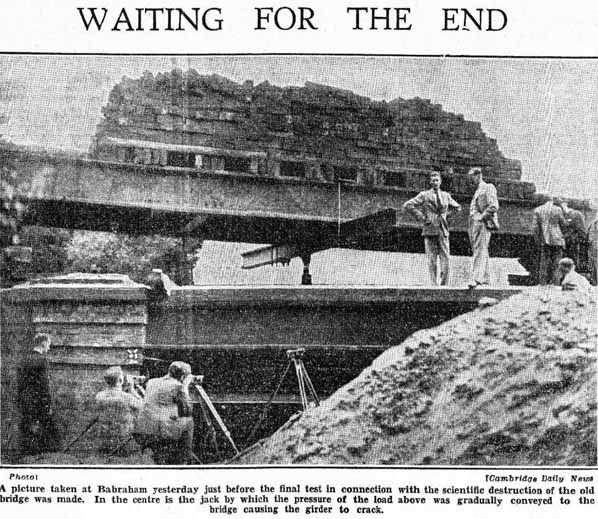

Subsequent to Kenneth Brown's photograph, the Abington Road bridge was either fully or partly demolished (it is unclear which) and infilled when the road, then a single carriageway, was widened in 1937. The demolition was in itself a curious business and thus thought worthy of inclusion here. The picture below is from Cambridge Daily News of Saturday 28 August 1937. It is of poor quality but as the original photograph is thought not to have survived we are fortunate that the newspaper article has.

Cambridge Daily News August 28 1937, reproduced by kind permission of

Cambridge Daily News August 28 1937, reproduced by kind permission of

The Cambridgeshire Collection.

The 'test' was undertaken by the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research in conjunction with the Ministry of Transport and Cambridgeshire County Council Roads and Bridges Department, as these bodies were then called. The Department of Scientific and Industrial Research was a government agency set up c1919 as an 'umbrella' organisation to oversee, as its name says, scientific and industrial research, and in the face of a perceived threat of Britain being overtaken by foreign nations following the First World War. The Department operated not just in Britain but also in much of the then British Empire and was finally disbanded in 1965.

The test was to determine the load-bearing strength of reinforced concrete beams. Babraham was by no means the only location to witness such 'scientific destructions' but a then-modern concrete beam bridge on a road that required widening must have been a rare opportunity for the people involved.

As can be seen from the picture, girders, presumably steel, were placed across the bridge deck and supported above it by what can be estimated as a height of around 3ft above the parapets. Stacked upon the girders are ingots of pig iron (the product of the initial process of iron ore smelting) and the ensemble is stated to have weighed 150 tons. Beneath the girders was placed a hydraulic jack which, one would assume, was operated remotely. When the hydraulic pump was operating, the weight above the jack would make the force of the jack progress downwards onto the bridge deck until, in theory, the bridge deck withstood the 150 ton weight which would then itself begin to move. Remember the school science lessons about 'Equal and opposite reactions'. The newspaper article is not too specific but it does state the experiment took three weeks to complete. From this we can surmise that the weight on the girders was increased incrementally until the bridge deck proved to be the weakest component. It is recorded that the deck fractured under a pressure of approximately 54 tons. But 54 tons is not 150 tons so why the apparent discrepancy? The girders carrying the pig iron were supported at each end, so much of the weight would be taken by those supports. This means that the unsupported central section of the girders would begin to flex with a force significantly less than 150 tons but higher than 54 tons - the point at which the bridge deck fractured. The fracture actually occurred the day prior to the newspaper being published, i.e. on Friday 27 August.

The picture is too unclear to be certain, but it would appear some kind of 'buffer' was placed beneath the bridge to prevent the whole lot collapsing completely into the cutting. On the other hand, the decking may well have collapsed into the cutting and been left there as part of the cutting infill. This is a question to which we simply do not know the answer. Whatever happened this was, in effect, the end of Abington Road bridge.

Moving ahead to the 1960s this stretch of road, for about one mile between Babraham and Four Went Ways (i.e. the A11 junction) was upgraded to dual carriageway. Cambridgeshire County Council records state this work was undertaken in two stages: Copley Hill Farm to Babraham Crossroads and from the latter to Four Went Ways. The additional carriageway was for eastbound traffic and thus was built on the north side of the existing carriageway. This work involved further infilling of the disused railway cutting and with it more evidence of the old bridge disappeared. In the 1990s further road alterations connected with the dualling of the A11 involved the realignment of a short stretch of what, by then, had become the A1307. This realignment resulted in the abandonment of the section of road once carried by the railway bridge, and today there is no indication whatsoever, other than the extant and overgrown railway cuttings to the north and south, that a bridge ever existed at this location.

If anybody can provide further, confirmed, information on this bridge and its reconstruction, especially in connection with any involvement by the Atlas Company, we would be pleased to hear from them.

Home Page

Home Page

Home Page

Home Page